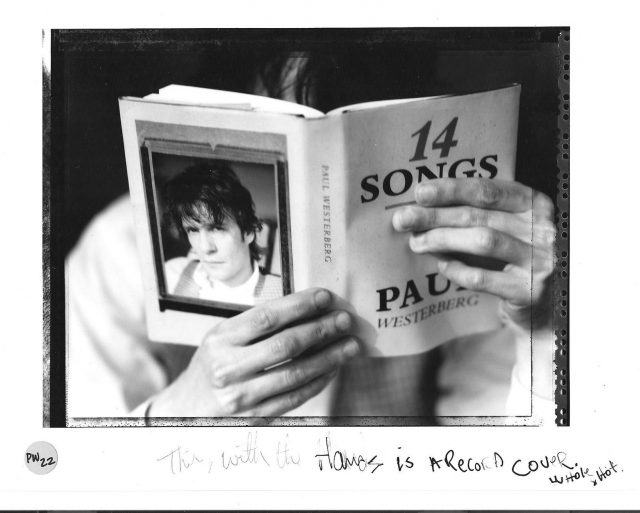

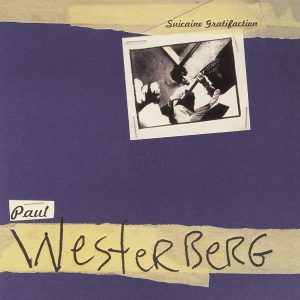

What can I say about Replacements singer-guitarist Paul Westerberg that hasn’t already been said far more eloquently by far more talented writers than me? Well, I can say this: I was lucky enough to speak with him just before he released Suicaine Gratifaction in 1999. And I do mean lucky: The next day, his publicist informed me that one of the writers after me asked him something that pissed him off enough that he called off the rest of his interviews. Glad that wasn’t me. Anyway, as usual, the bulk of our 20-minute talk ended up being cut for space. Here’s the full version. Hope you enjoy. I sure did.

Most rockers can’t live up to their rebellious reputations. Paul Westerberg just wishes he could live his down. “It sort of precedes me,” sighs the indie-rock legend from his Minneapolis home. “I spend my life calming it down, then I do one stupid thing and it flares up again.”

At least he comes by his notoriety honestly — Westerberg has always played against the rules. As leader of ’80s boozehound bashers The Replacements, he wed heart-tugging lyrics to bone-crushing riffs, laying the groundwork for grunge and paving the way for bands from Nirvana to Goo Goo Dolls. But his sharp tongue and rebellious nature also left him quite rightly branded as a loose cannon.

When the ’Mats broke up and he sobered up in ’91, Westerberg once again bucked the system. He grew up, settled down and blossomed into an introspective singer/songwriter, an evolution that continues on his darkly beautiful third CD Suicaine Gratifaction.

Over the years, he’s been called lots of things: alcoholic, misanthropic, eccentric. Congenial hasn’t been one of them. But that’s just how Westerberg was during our chat. Outgoing, wise-cracking and charming, he weighed in on his old band, his new record and his crushed rat brain.

What does Suicaine Gratifaction mean?

What does Suicaine Gratifaction mean?

It doesn’t have a meaning. It’s my made-up language. I’ll take two words, put them together and have a new meaning. It’s kind of a backwards, sideways thinking I use. It tips you off as to the content of the record, though.

It does have a dark resonance. And these are some of the saddest songs you’ve written. Is this a reflection of your life?

Yes (laughs).

And will you elaborate on that?

No (still laughing). To me, if you listen to the record, it’s obvious. I don’t sit down and make this stuff up. I take something and obsess on it. That was the case here. It was a bleak period, and I stuck myself in my studio and became a hermit. The stuff fed off itself and got darker and spookier. It’s the first time I’ve made a record of just serious material. There’s no stupid stuff on it.

Every story about you says you’ve matured. Do you feel mature?

I’m tired of hearing that myself. It’s a real simple and erroneous way to sum me up — ‘Now he’s mature, now he’s good.’ I was mature when I was 16, and I was immature last night. It’s just that my writing has gotten better.

It also seems to be headed somewhere. The songs are getting starker and the emotions are getting purer. Do you know how far you’re going to go?

No. That’s the beauty and the horror of it. I don’t know where I’m headed — yet my sixth sense tells me I’m on the right path.

Where does that path lead?

Well, I don’t think it’s a circle. I don’t think I’m going to come back to Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash. I think that I’ve broken the chain of what I once did. It feels like I’m starting over on a new road. I think it’s leading further and further away from structured songwriting. I guess in a perfect world, if I could knock off a standard song for another artist and make a living doing that, I think that my own work would get more and more poetic, out there, artistic. I just hope I can make a living doing this, because I’m not about to stop it at this point.

What is the songwriting process like for you? Do you get up every day and write, or do you wait for the muse to strike?

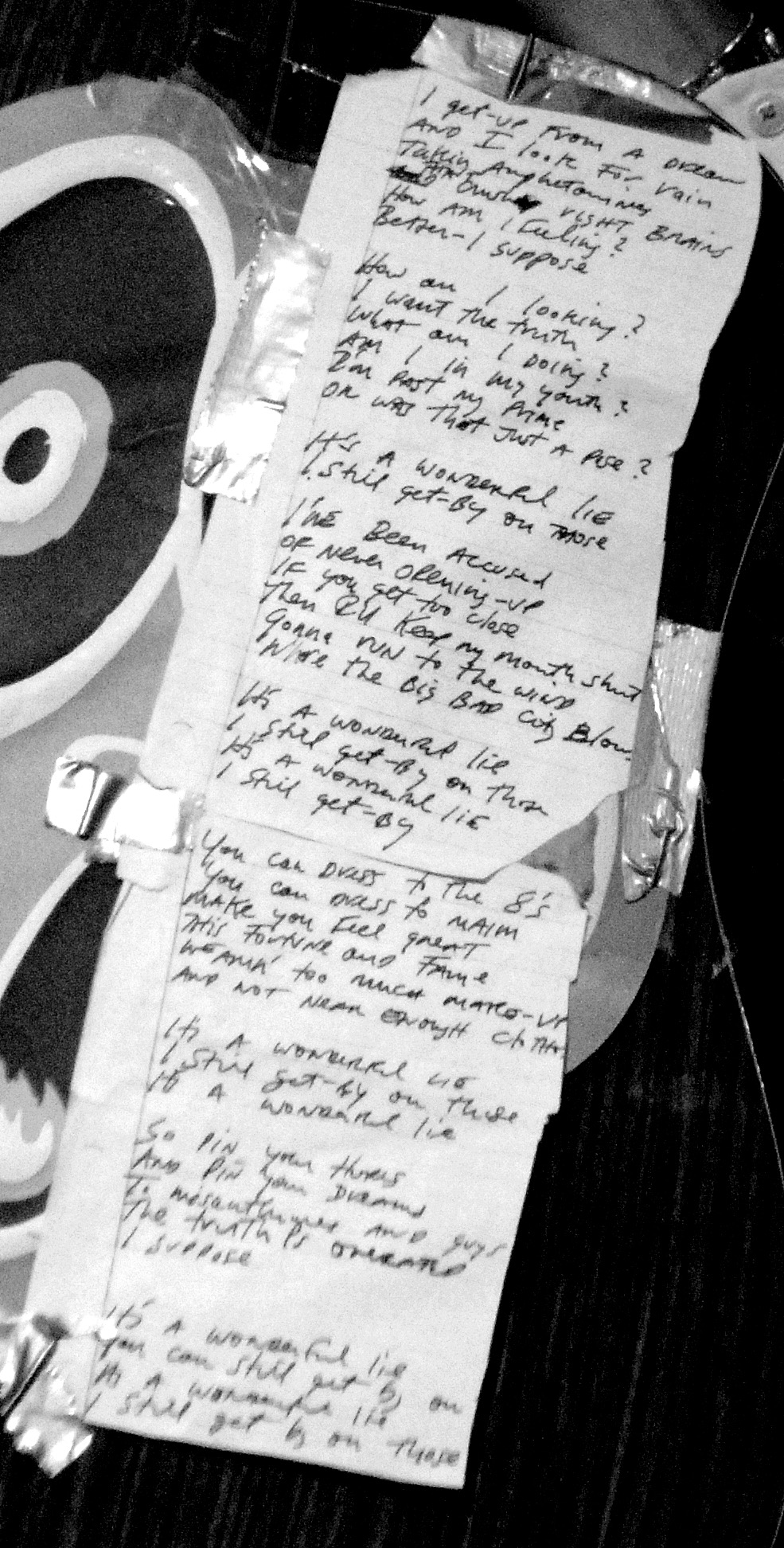

I wait for the muse. Without inspiration, it’s nothing but words. And cleverness without inspiration — well, he lives in England. I know that you’ve gotta wait for it, but sometimes you can’t wait. Sometimes you’ve just gotta get the ball rolling. I have a drawer right here full of scraps of paper and nursery rhymes and deep thoughts and everything possible. I keep adding to it until I feel the need to bust through and write one. Right now, I’m not feeling on top of my game — plus I’m doing interviews — so it’s hard to break away and write a song. But when it starts, it’s hard to stop. I wrote six or seven of these right in a row. There was two weeks in October — what year it was, I’m not sure — where I just stuck myself in my little studio and practically lived down there. I became like a hermit. The stuff fed off each other. It got darker and darker and spookier. I left a few of them off.

Where does Grandpaboy’s stuff fit in with all this?

I did that in the midwinter. It was for two reasons: One, I was off of my record deal with Warners. For the first time in 11, 12 years, I was without a deal. So I was free to do anything I wanted. So I kind of jumped at the chance to record and get something out there for fun. And the other thing is that I’d sort of run dry of this first wave and felt like rocking a little bit. So it’s kind of a rockabilly thing. Yet there is a song on that that I couldn’t wait two, three years to come out on the record. So I kind of slipped that in there: Lush And Green. One listen to that and you hear where it would have lain right between things for me.

https://youtu.be/DRr-2ntbJfo

Don Was seemed a kind of curious choice as a producer. People were wondering if you were gonna sound like Bonnie Raitt or the Rolling Stones now.

I wanted Quincy Jones. No, I seriously did. We sort of went after him two or three times, and he said he was busy with other things very cordially. It’s like hiring a guitar player who likes exactly the same things and does the same things as you. You’re not going to break free and get anything new. I want to learn. And there’s so many producers that can’t teach me anything.

What did Don Was teach you?

Well, I think I taught Don a few things. But he taught me when to leave well enough alone. The reason I think I hired him is that we both wanted it to be simple. But even though I wanted that, I’m still a putzer — ‘Let’s put another guitar on here’ and ‘Let me put another voice’ and ‘Let me do another and another’ — to the point where I’ve wrecked it. He knows if it’s done, it’s done. You stand away from it and you move on. I needed someone to listen to what I’ve done and say, ‘Hey that’s nice, but you were better with the original take.’

These days, what satisfies you as an artist?

Nothing satisfies me, really. I don’t know who said it, but it’s like ‘All artists have a divine dissatisfaction with what they do.’ It’s true. I’m never truly satisfied or happy with what I do. But there’s a moment where it stops gnawing at me. That’s usually the sort of moment when I go, ‘A-ha! This title and this melody are going to work.’ It puts a smile on your face and it might even give you a chill for a second. But it’s work. It’s not real fun. It’s fun later when you get to play it for somebody and then you travel to a studio and you spend half a million dollars putting a trumpet on it, you know.

What motivates you to do it if it’s not fun and it’s so much work? Aside from paying the rent?

I don’t know. The rent is getting paid. It’s all relative — rich, poor, whatever. But I don’t have to go out and work at McDonald’s.

But it’s not commercial success that you’re pursuing.

It isn’t and thankfully not. Commercial success comes and goes. But I think what I’ve got going would take me 12 years to unravel. It’s not an overnight thing that it could suddenly be ‘Oh, he’s no longer credible. He sucks.’ I have a back catalogue of like 100 songs. Maybe 50 of them are solid or worthy. Maybe 10 of them are truly, truly great. I don’t know. I guess I do it because I instinctively know that this is something that I do better than most people in the world.

What do you listen to these days?

Good question. I’m kind of divorced from the radio. I don’t listen like I once did. I’ve been in a funky way about the last month and a half. I barely even watch the television. I think I’ve just been overdosed with the repetitive nature of everything from the presidential crap to turning on the radio and saying, ‘Oh, that song again,’ or ‘That style singer again.’ I listen to John Coltrane when I want to forget about music. It’s almost beyond music. I can’t just put it on and vacuum the floor. I have to sit there transfixed. There’s nothing that comes on the radio that actually grabs my attention like that.

Talking about commercial success, what do you think about Johnny Rzeznik and The Goo Goo Dolls having such success treading the same path you laid down so many years ago?

In a strange way, it’s good for me too. If we can split the pie down the middle and say, ‘Johnny, you take the money and the fame,’ what does that leave me? The credibility. Every single article that he does, they mention me. I can’t look badly at that. Johnny learned from me, he imitated me — he admits it, he’s a man about it.

But isn’t there a small part of you that says, ‘That should be me’?

When I was 28, yeah. I don’t envy him now. I know the way he’s done it and I refuse to do it. You kiss one ass and you’ve gotta kiss ’em all. You kiss ’em once and you gotta kiss ’em twice. I was never about that. I couldn’t bear to go and play for those radio station Christmas parties. It’s all about playing the game to get the spoils. I was never that, The Replacements were never that, I’ll never be that.

What about playing in general? Are you going to tour behind this album?

Maybe long behind it. (Laughs). I don’t have the gumption to get up and open my mouth in front of people.

Does it tick you off when people yell for Replacements songs when you’ve done so much since then?

I don’t mind that stuff. That’s all good. I’ve never been a live performer who’s felt, ‘They’re not listening to my new material.’ I understand totally. You go see Lou Reed, you wanna hear the songs that made him Lou Reed.

It’s been almost eight years. How do you look back on The Replacements now?

Like they were my first real love. Almost my teenage girlfriend or something. I look back fondly. They’ll always be No. 1 in my heart. Or some crap like that. But I couldn’t bear to hang out with them. And they feel the same way. We did it; we did it to the hilt. We don’t feel like getting back together or anything. People think we must be mad at each other or else we’d be playing together. It’s almost the opposite. We stopped playing so we could continue to actually be friends. It was like a divorce — ‘We’re going to kill each other if we don’t break up.’

You’re turning 40. Do you think you’re heading for a midlife crisis?

I think I passed it. I think that’s what going to be released.

So the album is the soundtrack to your midlife crisis?

It’s probably my second or third one, because I feel like I’ve been through stuff early. It’s not a mental thing of, ‘Oh, I feel like an old man.’ I mean, I physically feel beat-up, but that happens occasionally.

Do you still have any bad habits? You don’t drink anymore, right?

No, I don’t. As for chemical habits, well, I’ve had to take pills for my back recently which sort of help on one hand — and on the other hand is kind of fun. I’ve taken all kinds of things that chemists and physicians advised that will make your life better or different. The very first line of It’s A Wonderful Lie spells it out. Taking amphetamine for a crushed rat brain. They ask, ‘What’s a crushed rat brain?’ Well, I know what it is. I bet someone else who takes one does too.