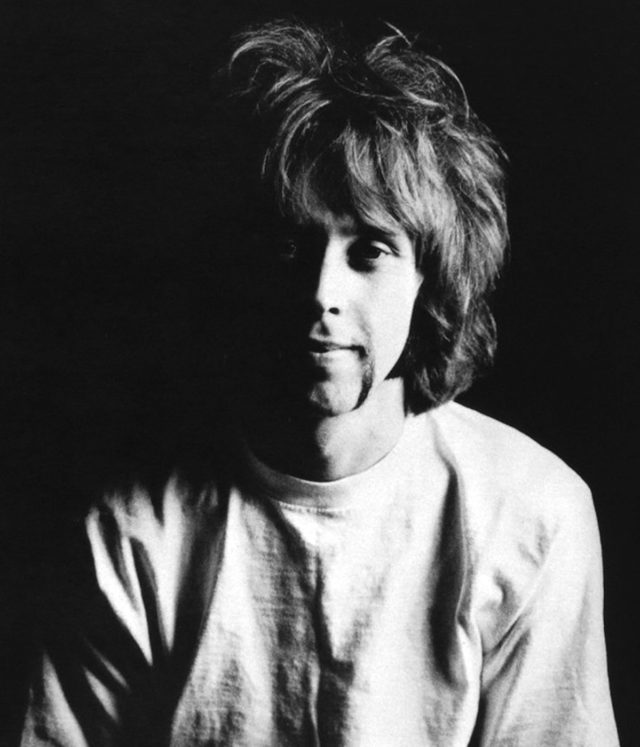

The Monterey International Pop Festival happened over the course of three days — a Friday night show, Saturday and Sunday matinées and corresponding evening shows on June 16–18, 1967. Kicking off the big Saturday night event was one of San Francisco’s latest acts (though none of them were local boys): Moby Grape. All five members could sing lead, they all wrote and they could play like hell. But, as they ripped into their set-opener, Hey Grandma, it was guitarist and vocalist Alexander “Skip” Spence who captivated the crowd and kept their attention throughout.

The Monterey International Pop Festival happened over the course of three days — a Friday night show, Saturday and Sunday matinées and corresponding evening shows on June 16–18, 1967. Kicking off the big Saturday night event was one of San Francisco’s latest acts (though none of them were local boys): Moby Grape. All five members could sing lead, they all wrote and they could play like hell. But, as they ripped into their set-opener, Hey Grandma, it was guitarist and vocalist Alexander “Skip” Spence who captivated the crowd and kept their attention throughout.

Spence takes the lead vocal on Hey Grandma, which was written by drummer Don Stevenson (who angered Columbia by not-so-subtly giving the finger on the cover of the band’s self-titled ’67 debut) and lead guitarist Jerry Miller, who just passed away on July 20, only two weeks after his 81st birthday. The impish, wild, Spence was known to the crowd as the flamboyant drummer on Jefferson Airplane’s debut album, Takes Off (1966) — the high point of a nine-month gig that he got because he looked the part. He also jammed with an early incarnation of Quicksilver Messenger Service and turned down the drummer role in Buffalo Springfield for the rhythm-guitar job in Moby Grape. Despite being fired by Jefferson Airplane for an unapproved Mexican vacation, Skip was in demand. Back at the front of the stage, in a band he co-founded, Spence was at the top of his game. He was never better — a poster boy for San Francisco’s music scene, but wasn’t from there.

If you met him at the time, he might have told you he was from Dayton, Phoenix or San Jose — the latter is where his family settled in 1960 after a nomadic few years. Spence’s father, Alexander Lett “Jock” Spence, was a Canadian who applied for U.S. residency after returning from the Second World War. The decorated RCAF bomber pilot was denied due to a fraud charge from his youth, so he appealed. He had transitioned from vacuum-cleaner salesman to full-time musician when his appeal was approved in July 1949. The family — Jock, wife Gwenn and kids Skip, 3, and one year-old Sherry — moved to Detroit on Aug. 1, 1949. This was because Jock still had to finish a run of residency gigs at Windsor’s old Commodore Club on Chatham Street (now Alley Katz strip club). Jock did a cross-border commute until his residency ended Sept. 25, 1949, after which the family moved briefly to Kentucky. They returned to Canada for a bit when Gwenn’s father died, but left again in November, never to return. There were stints in Detroit (again), Knoxville, Tenn., and in Portsmouth and Dayton, Ohio.

Jock’s biggest gig as a professional musician came in Dayton, where he played the historic Biltmore Hotel every night for three months. But mostly, he was gigging all over Ohio — so at the end of 1953 the family decided to go in search of stability in Phoenix, Ariz. This was the adopted home of Jock’s father, Alex Llewellyn Spence who emigrated with his wife Vi and son Paul from Windsor in December, 1946.

Jock and his young family lived in an Airstream at the Evergreen Trailer Park in Phoenix. Jock worked as a traveling salesman and musician, mailing letters and money back home to Gwenn and the kids. That’s where they were living in 1956, when some of that money was used to buy Skip his first guitar. A year later, travelling Jock came home and told the family they were going to California. In the summer of 1957, they made the drive to Oakland and settled in Hayward, across the bay from San Mateo. They stayed there for a year before relocating yet again a half-hour north to Walnut Creek for two years, before finally arriving in San Jose in 1960 when Skip was 14 years old. It had been more than a decade since he left Canada.

Alexander Lee Spence was born April 18, 1946 at Hotel Dieu Hospital in Windsor. His sister Sherry was born there, too on June 12, 1948. At the time of Skip’s birth, the family was living at 2237 Howard Ave., an address which doesn’t appear to exist anymore. While Skip wasn’t even school age when he left Canada, his roots here run deep — and involve a number of places which are quite familiar to me.

Jock was born Dec. 29, 1914 in Flower Station, Ont., on the east shore of Flower Round Lake. This is a small rural community in Lanark County — about 40 minutes northwest of Perth. It was a stop on the old K&P (Kingston & Pembroke), railway which had 26 stations between Renfrew in the north and Kingston in the south. Going from north to south, Flower was the sixth station. The rail line has been converted into the K&P Trail, which has three sections. You can walk or bike through Flower Station on the middle section, which runs between Barryvale on Calabogie Lake in Renfrew County and the old mining ghost town of Wilbur in North Frontenac.

Jock’s fathe was born July 5, 1890 in Fergus, Ont., north of Kitchener (then still known as Berlin) and Guelph — which was only incorporated as a city 11 years earlier. Alex Llewellyyn was one of three kids born to John and Mary Ann Spence. John died not long after Alex’s birth in 1890. Alex briefly had a new stepfather when widow Mary Ann married widower Bill Crickmore — who, like The Brady Bunch, came with three kids of his own. He and Mary Ann had a daughter, Myrtle Crickmore, born in Fergus in 1896.

Jock’s mother was Elizabeth “Effie” Deachman, born May 19, 1893 in Flower Station. Effie’s parents were Alexander Monroe “Sandy” Deachman and Margaret Catherine Lett — both of Lanark County. Jock’s parents, Effie and Alex, married in 1912 in Saskatoon. Their first child Vivian was born in Saskatoon, but Jock was born a year later in Flower Station. Alex and Effie divorced and Effie remarried in Brockville, Ont., to a man named Clarence Giffen. They kept a cottage on Flower Round Lake called Fairvale. Jock’s dad Alex remarried as well, to Vivian “Vi” Rose Saunders, in Windsor in 1938. Together they had a son named Paul, Jock’s half-brother.

In the summer of 1952 or 1953, Skip and his family took a summer vacation, staying with Effie and Clarence at Fairvale. Even though his father was buried not far away at Clyde Fork Cemetery in May 1965, Skip never returned to the area after visiting that one summer. The closest he came were some New York shows with Moby Grape. The only time he returned to Canada at all after that summer in Lanark was a run of five shows in January ’66 with Jefferson Airplane in Vancouver. His last show with the Airplane was June 4, 1966 after manager Matthew Katz managed to find a replacement. The Spence-penned My Best Friend was included on the band’s sophomore album, 1967’s Surrealistic Pillow, despite him no longer being in the group.

Exactly one week after Moby Grape played Monterey, Skip found himself within a four-hour drive of his Ohio childhood home when the band played in Cleveland. In December of that year, the band went further into Skip’s past with two shows on the 8th and 9th at Detroit’s famed Grande Ballroom. By this time, the increasingly erratic Spence was beginning to fall apart. Moby Grape only played Canada once during this era — five shows in five days at Vancouver’s The Cave from Aug. 6-10, 1968 — but by then, Skip was gone from the band. He was admitted to Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital in New York in June, where he remained for six months.

The split happened while they were recording their second studio album Wow in New York in September 1967. According to Miller, Spence tried to break down his door at the historic Albert Hotel in Greenwich Village using a fire axe. But the other Grape guitarist Peter Lewis says it was drummer Stevenson whose door was the target of Skip’s axe. Lewis says he left the band in New York during the Wow sessions and went back to California. He says the band came back and played a gig at the Fillmore without him. During this engagement, Lewis says, Spence was given a heavy dose of LSD and was never the same.

It seems Spence’s increasing drug intake was evidence the musician was self-medicating. While in Bellevue, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Still, he was offered a contract by Columbia and went directly to their Nashville studio upon his release and recorded his only solo album, Oar. The record is a difficult listen, as it is made up of songs written by Spence at Bellevue and performed entirely by himself. At their core, these songs are quite brilliant — as evidenced by the 1999 tribute album More Oar, which sees the entire record covered by artist fans including Robert Plant, Beck, Tom Waits, Mark Lanegan and Flaming Lips. The goal was to raise funds to help cover the songwriter’s medical bills. More Oar was finished in time to be played for Spence on his deathbed.

For years, Oar was considered the worst-selling record Columbia ever pressed. It has since, of course, seen subsequent audiophile pressings and is considered an outsider classic. It was the last record Spence would ever fully contribute to, but he continued to make and play music — as much as his mental illness and colossal drug and alcohol consumption would allow. He founded and experimented with a three-man rock band called Pachuca and later a bigger group who called themselves The Rhythm Dukes. He cut the incredible All My Life (I Love You) in 1972 and continued to have minor involvement with Moby Grape, contributing to their 1971 album 20 Granite Creek, playing a run of reunion shows that year and appearing on 1978’s Live Grape. It was Moby Grape’s practice to always include something from Spence, whether he could participate or not. But mental illness and addiction prevented him from being able to make a living at music, or anything else. He spent a great amount of time in care, as a ward of the state in halfway houses or unhoused.

In 1994, Spence took part in a music program for the mentally ill, put on by the city of San Jose. Through this, he was commissioned to contribute to the soundtrack of the upcoming X-Files film. The song Spence came up with was the haunting Land Of The Sun — which, sadly, wasn’t chosen for the film. You can get it on a double A-side single, paired with All My Life (I Love You), or included on the More Oar tribute. Neither of those tracks are on Spotify.

Spence’s final live performance was with Moby Grape on Aug. 9, 1996 in Santa Cruz. He died of lung cancer on April 16, 1999. He is survived by four children — Aaron, 60, Adam, 58, Omar, 56 and Heather, 54 — along with 11 grandchildren, his half-brother Rich Young, and his sister Sherry Ferreira.

Going back to where we started at Monterey: Spence was one of several Canadians who performed at the legendary event. Bruce Palmer (Liverpool, NS) played bass for Buffalo Springfield but Neil Young (Toronto / Winnipeg) was a no-show. Denny Doherty (Halifax) performed with The Mamas & The Papas. And, let’s not forget Toronto’s The Paupers, who performed second on the opening night of the festival. They were made up of future Lighthouse leader Skip Prokop (Hamilton), Denny Gerrard (Toronto), Adam Mitchell (Glasgow / Toronto), and Chuck Beal (Toronto).

There is no Canadian memorial or marker for Spence that I’m aware of. Windsor Public Library has a page dedicated to him.

I fashioned a playlist of some great Spencer songs — as a drummer, a vocalist and guitarist, or simply as the songwriter.

Many thanks to Cam Cobb for researching the Spence family history in Canada in his new book, Weighted Down: The Complicated Life of Skip Spence.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.