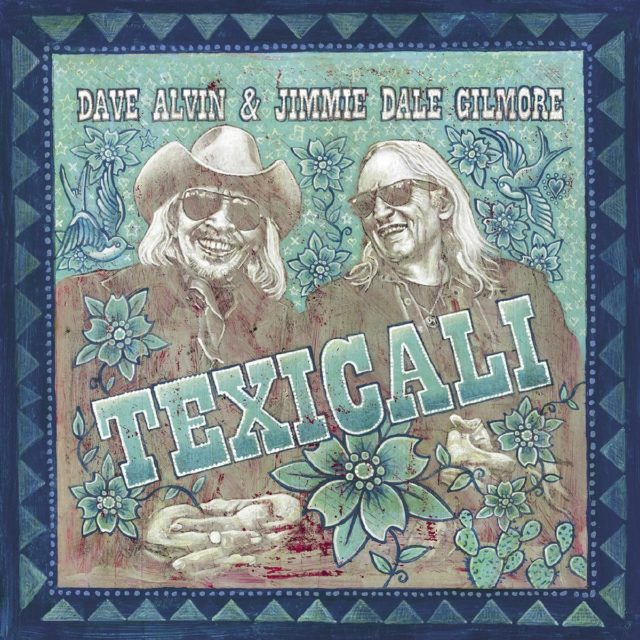

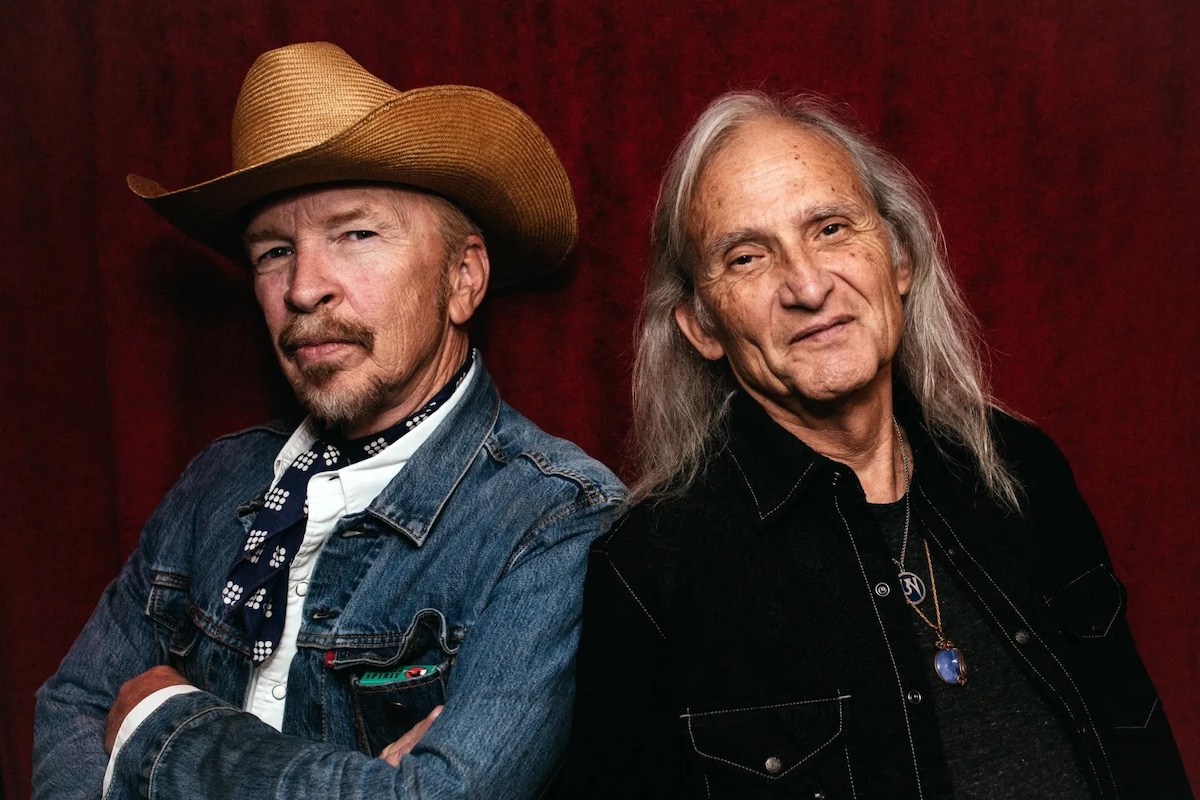

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “When Grammy winner Dave Alvin and Grammy nominee Jimmie Dale Gilmore made the album Downey To Lubbock together in 2018, they wrote the title track as a sort of mission statement. “I know someday this old highway’s gonna come to an end,” Alvin sings near the song’s conclusion. Gilmore answers: “But I know when it does you’re going to be my friend.”

Six years later, they’re serving notice that the old highway hasn’t ended yet. “We’re still standing, no matter what you might hear,” they sing on We’re Still Here, the final track to their new album TexiCali, an LP that continues to bridge the distance between the two troubadours’ respective home bases of California (Alvin) and Texas (Gilmore).

The geographic theme reflects Alvin’s repeated journeys to record in Central Texas with Gilmore and the Austin-based backing band that has toured with the duo for the past few years. As Alvin puts it in the liner notes, those road trips informed the music they made on TexiCali:

“From one part of the borderland to another, through concrete swaths of traffic, tract homes and shopping malls, across vast rocky deserts of Joshua trees, saguaros and ocotillo, speeding by forgotten battlefields, remote mining towns, corrido barrooms, cinder block churches and abandoned houses filled with abandoned dreams, past Mission San Xavier del Bac, Cochise’s Stronghold and Apache Pass, into the shimmering lights of El Paso/Juarez before the seemingly eternal emptiness of West Texas, traveling those 1,400 miles somewhere between Nothingness and Everything.”

This panoramic spirit seeps into songs such as Southwest Chief, which Alvin started years ago with New England songwriter Bill Morrissey and finished after his death in 2011. Alvin framed the song with memories of the Roots On The Rails train tours he did with fellow musicians for a dozen years. “We’d stack vintage cars on the back of an Amtrak train” and then play for the passengers en route, Alvin explained. On the final tour in 2018, “we were attached on the ride back from Chicago onto the legendary Southwest Chief.” Recounting visions en route of prairie sunrises, the land of the Navajo and the Mojave desert, Alvin concludes: “Southwest Chief, let your whistle blow / Wherever you’re heading, I want to go.”

A similarly wide-open perspective imbues Down The 285 by Austin songwriter Josh White, who died in 2012 at age 28. Gilmore first recorded the song on an obscure compilation paying tribute to White. With its enchanting “I can’t take my eyes off the moon” refrain, the song captures the feel of rolling across New Mexico toward Texas at night on a desolate stretch of U.S. Highway 285.

The 11 songs on TexiCali also connect the duo’s shared fondness for a broad range of American music forms. On their own, both have been prominent artists for decades. A philosophical songwriter with a captivating, almost mystical voice, Gilmore co-founded influential Lubbock group The Flatlanders with fellow singer-songwriters Joe Ely and Butch Hancock in the early 1970s. Alvin, meanwhile, first drew attention as a firebrand guitarist and budding young songwriter with his brother Phil in Los Angeles roots-rockers The Blasters in the early 1980s.

Gilmore is primarily known for left-of-center country music, while Alvin’s compass points largely toward old-school blues. But there’s a lot of ground to cover beyond those foundations, and both artists also are well-known for transcending genre limitations. So it’s not surprising that they’ve spiked TexiCali with cosmic folk narratives, deep R&B grooves and even swinging reggae rhythms. “There’s such a strange variety through the whole thing,” Gilmore says. “And I love that.”

They’re both quick to credit the musicians who joined them in the studio as crucial to the sound and spirit of the album. On their previous album Downey To Lubbock, they recorded primarily in Los Angeles with a crew that included ringers such as the late Don Heffington on drums and Van Dyke Parks on accordion. This time, though, Alvin’s longtime rhythm section of drummer Lisa Pankratz and bassist Brad Fordham played a larger role, along with guitarist Chris Miller and keyboardist Bukka Allen. “After the time we spent touring, Jimmie and I became members of this band,” Alvin says. “The band can play just about anything, which the album shows off.”

They recorded much of TexiCali in several 2023 sessions at The Zone recording studio just outside of Austin, which is home for Pankratz and Fordham as well as Gilmore. “That’s why it was worth the drives down I-10 to Austin and back to California,” Alvin continues, “to get everybody together and capture what a good band it is.” Gilmore concurs. “The band genuinely created a lot of what this record is,” he says. “It wasn’t pieced together by studio musicians; it was a whole thing made by a real band.”

TexiCali also found Alvin and Gilmore increasingly focusing on original material. That wasn’t necessarily a goal or gameplan, they both say — but when it came time to select songs for the sessions, more than half of those that made the cut were tunes they wrote or co-wrote. Among them are Trying To Be Free, which Gilmore wrote more than 50 years ago, and Death Of The Last Stripper, which Alvin wrote with Terry Allen and his wife Jo Harvey Allen. There’s also a fresh take on Borderland, a song from Gilmore’s 1996 album Braver Newer World, and Alvin’s bluesy Blind Owl, a tribute to Canned Heat co-founder Alan Wilson.

Just as important, however, are the choices they made for non-original material. Any projects that involve Gilmore invariably will lead to a song by his longtime friend and Flatlanders bandmater Hancock. Thus we get the hypnotic Roll Around, set apart by the reggae-tinged playing of Pankratz, Fordham and Miller.

Elsewhere, Alvin pushed Gilmore to explore the full range of his voice. “I think Jimmie is one of the great contemporary blues singers,” Alvin says, explaining why they recorded the Blind Willie McTell staple Broke Down Engine. And their take on Stonewall Jackson’s That’s Why I’m Walking marries Gilmore’s country croon to a New Orleans R&B arrangement. Gilmore says, “I love New Orleans music, “but it’s not the music I play.” Dave slyly counters: “It is now!”

But it’s Brownie McGhee’s Betty And Dupree that strikes closest to the heart of this musical partnership. Their first album together also included a McGhee song, Walk On. Long before they knew each other, a teenage Alvin and a twentysomething Gilmore got to hear folk-blues legend McGhee (with his longtime partner Sonny Terry) at L.A. blues club the Ash Grove, during Gilmore’s brief time in California in the late ’60s. Gilmore actually befriended McGhee during a short stay in the Bay Area, where Tennessee native McGhee resided in his later years.

Alvin recalls how they discovered these connections when they first toured together as an acoustic duo in 2017. “Jimmie would pull out something and I’d be like, ‘Wow, you know that song?’ And if I was feeling comfortable, I’d chime in singing. So (the McGhee covers) are a way of harkening back to those early few months of touring together.” Jimmie agrees: “Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee were part of the group of people that Dave and I had both been deeply influenced. It’s a real good example of the glue that keeps Dave and me together.” So will there be another Alvin / Gilmore record? And if so, will they turn to McGhee’s songbook once again? Alvin doesn’t hesitate: “Yeah!”