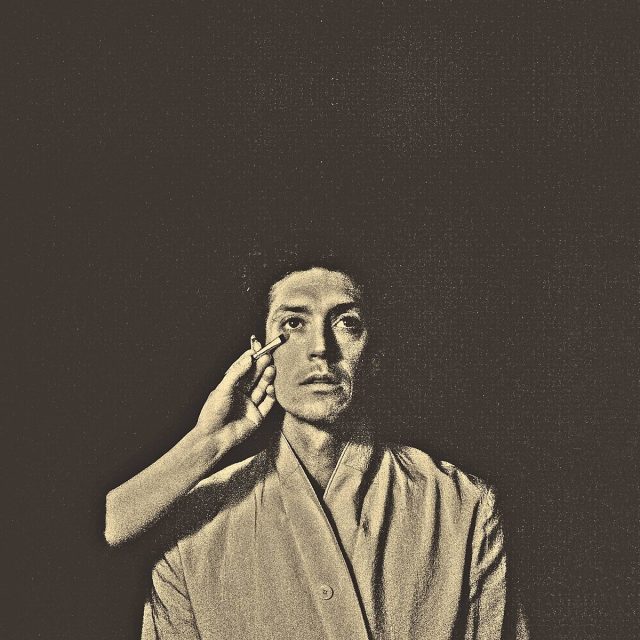

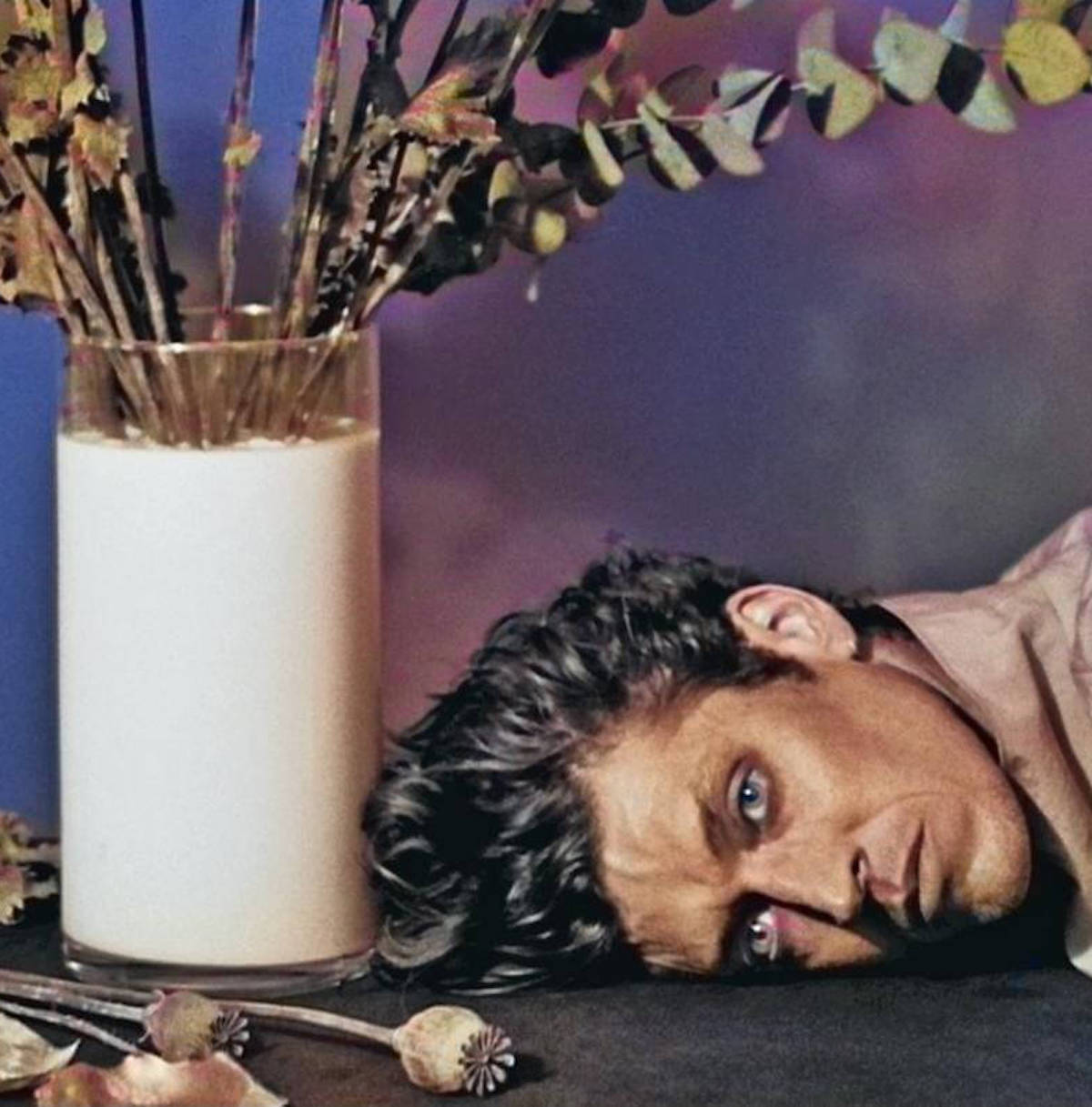

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “ A nun gathers roses in the pouring rain, their thorns piercing her thumbs. A bittersweet perfume hangs in the air of a milk-warm night as beloved hands and feet are sculpted in the marble of memory, and waxen votives melt at the altar of a merciless god. On Milk For Flowers, beauty flourishes in the corners of grief’s desecrated church; jewelling the cobwebs, gilding the dust, and making a relic of its creator’s arrow-shot heart.

Brought to being in Huw Evans’ hometown of Cardiff, the writing of the album served as the outlet for several dances with the violence of life — a spate of significant events which took his spectrum of emotion and experience suddenly widescreen. Where 2017’s I Romanticize and 2015’s In The Pink Of Condition might be thought of as dadaist art objects — feeling and meaning obfuscated by the absurd — Milk For Flowers belongs firmly in the realm of the divine; not only for the auspices, saints and holy bakers that populate its lyrics, but also for its exquisite torment; the gateway to a newfound profundity of voice.

“I’m not so good at showing vulnerability and I think that’s why, in the past, there’s been a tendency to obscure or make abstract any real emotion, either lyrically or musically,” Evans reflects. “I think this was most apparent with the way I sang, keeping everything as flat and emotionless as possible. It was impossible to do any of those things with this album: I had to sing.”

Milk For Flowers is at once visceral and enlightened, its soundscapes verdant yet delicately rendered. It opens on its title track; a piano-driven masterwork which finds Evans on his knees, tight bud of voice and arrangement bursting into head of rich velvet petals and peals. “I don’t need happiness now,” he sings, opening the door to a melancholia which seeps through the album’s 10 tracks, its pigment ever-more concentrated with each song. “Help me, help me, help me,” he begs on Plastic Man, in which he is a “lizard stuck on a stone / trying to call home.” On Suppression Street, he is hollowed by grief, vocals haunting themselves, embodying his words (“someone call the doctor, I’m an echo”) as he paints on a new face for show.

His plight is relentless, but refracted through his pen and pedals, it is also breathtaking; as clear and sharp and pure as shards of glass pushed between the listener’s ribs. As Denver rises, blinking, from the mist, a transcendent choir of H. Hawklines carry the presence of the lost in their veins with a love that never becomes too much. On Mostly, starry keys and the warmth of brass soften the devastating directness with which he confronts mortality (“I want to die happy / Nobody home to hear me call for the seabird to take me”) and on Empty Room, pedal steel takes on an otherworldliness as it washes around a confession as raw as they come: my dad doesn’t sleep anymore. Be as it may that Evans’ feelings are worn so freshly and visibly on his sleeve, Milk For Flowers also carries his unmistakable emblems: Poetic and yet unexpected elegancies of phrase (“Peace comes for dinner, but I’m forever eating lunch,” he laments on Mostly; “Found her face about a lover too soon, folded like a rabbit in the road,” he professes on I Need Him — entire worlds conjured and collapsed in the span of a single sentence) and effortless, irresistible musicianship of no fixed genre (Athens At Night stabs and slides, its riffs simultaneously liquid and punchy; the wavering steel of Empty Room conjures wide American skies; It’s A Living spills a cascade of keys onto a taut rhythmic backdrop, by turns disciplined and freeform).

A continual collaborator, H. Hawkline is one of a circle of likeminded friends and artists quietly and perpetually party to, enthusing about and augmenting each other!s works-in-progress, all for the love of the making, and never fully, if at all, recognised for their contributions. Of particular note is his toothlong creative relationship with the celebrated solo artist, fellow enthusiastic collaborator and producer Cate Le Bon, each having contributed to every one of the other’s albums over the last decade-and-a-half — an alchemical meeting of minds which pushes both artists! practices in ever more shining directions. It was Le Bon who recognised the familiarity required to consign Milk For Flowers’ tenderness to tape, and, taking on the role of producer. “With a gentle and knowing hand, Cate did what no one else could have done: it’s what Cate always does,” surmises Evans. Her subtle presence on Milk For Flowers is as much heard as felt; in the brass embers of Denver and Mostly, the unearthly synth-line of Like You Do, the recurrent to-and-fro of percussive layers which almost but never quite collide.

Seeking geographical as well as human familiarity, Evans and Le Bon laid the album down at Rockfield Studios in Monmouthshire, furnished with a personnel of mutual collaborators: Davey Newington (Boy Azooga) on drums, Paul Jones (Group Listening) on piano, Tim Presley (White Fence, DRINKS, The Fall) on guitar, Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo) and Euan Hinshelwood (Younghusband, Cate Le Bon) on sax, Harry Bohay (Aldous Harding) on pedal steel and John Parish (PJ Harvey, Aldous Harding) on infrequent bongo. The record was then engineered by Joe Jones (Parquet Courts) and mixed, after an unlikely and fortuitous crossing of paths, by the Grammy-nominated Patrik Berger (Charli XCX, Robyn, Lana Del Rey) and mastered by Heba Kadry (Deerhunter, Cass McCombs, Cate Le Bon).

With this latest, most intimate work, H. Hawkline beautifully bares his blood, bones and soul. And quietly, along with the entrails and rubble held in Milk For Flowers’ reliquary, there hides a small, green kernel of life; hope, perhaps, that today!s decay might nourish tomorrow!s blooms.”