“The meaning of life is that it stops.”

— Franz Kafka

It was a sunny day. I remember that much. The fuzz of sunshine joists crashing through the blinds. Elasticated seams of light reaching for and swirling into the dumpy cigarette smoke, the heaviness of the fried meat funk, the fog of a sad strange war that teased me and repelled me at the same time. The whole scene was lovely and broken, like so many other rooms I would know in the years to come.

It was a sunny day. I remember that much. The fuzz of sunshine joists crashing through the blinds. Elasticated seams of light reaching for and swirling into the dumpy cigarette smoke, the heaviness of the fried meat funk, the fog of a sad strange war that teased me and repelled me at the same time. The whole scene was lovely and broken, like so many other rooms I would know in the years to come.

I was 9, maybe 10. I loved fishing and baseball and MTV.

And I had never seen a real pair of lady tits until now.

Merry was in her late 30’s at that point, standing in the dining room with jeans on, and no shirt. Her flowing hair was straight and gray already from the bar rooms and the late nights and whatever rough life she had known up until then. I saw it as silver though, her hair. Silver hair, like a waterfall. Like some disturbing spring runoff mess plunging to its untimely end. Her eyes were grey. Or blue. Or both. Maybe one of each since time allows for such minor tweaks in the narrative, I think. One grey eye and one blue eye staring at me, the older one, the older son of the man she had joined forces with, just a young kid standing right inside the front door.

I must have knocked, I tell myself, but I don’t honestly know if I did. Who even cares at this point, you know? Details die if you hardly feed them. I have locked a lot of incidents away for centuries. And still, some stuff I recall. Like her voice. Merry’s voice. It was a crow’s caw. The sound of her was heat vent hiss. It rose up out in bursting puffs of excited New Englander. Her accent was chowder-y. Her lungs pushing unabashed curses up through the cancer-y wood lot infesting her pipes. Everything she said was run through her musket barrel esophagus. Crass and crude street smarts shot up like flushed grouse through her duct work of dagger thorns and pricker bushes.

Merry talked like she’d been knee’d forward to give a little surprise talk at church. Egged on by a molesting uncle, just a little girl preaching her so-called truth.

Merry’s rasp was the passing truck and the rest of the us were the good dishes hiding in the vibrating china closet.

Hey. Come on in.

I know I heard her holler that from inside the house after I’d knocked or rung the bell.

But I don’t know.

Fact is, I was inside after I was outside, past the front door, looking for time with my dad: hoping, I imagine, to firm up some plans with him to meet early on Saturday morning so he could take me bass fishing at the river. Those fishing mornings, seldom and undependable as they were, remained the last bastion of anything shared between me and my dad. Even now, they stand as just that. The last times he took me with him. The last times he seemed remotely interested.

That day though, in my old house, the home where I had been taken to straight from the hospital after I was born, there I was. Serge, The Son of Serge. And there she was, Merry, my dad’s girlfriend, standing right on the spot where my mom had once weeped heavy snot and tears down into my cereal the morning John Lennon’s death had broke the world.

Merry in her big wide-hip jeans, her tennis sneakers, her platinum witch’s hair, standing there looking at me, me standing there looking at her. Her massive sagging pancake tits were on full display. She had been walking around the house like that. Living her life, smoking her menthols, probably having a drink. The first beer of the afternoon maybe. Probably not though.

It was as if I were looking at a killer whale on the floor of the old house, its belly slit open and its heaving, heavy guts shining out through the layers of darkness that floated across the weak illumination trying desperately to penetrate the room.

It was as if she was stood there pointing a shotgun at my head.

It was as if I had walked in on time stopping. Sensitivity dying. The shock of the unexpected twist. The audacity of the R-rated creepiness. I had no idea where my dad was. I don’t remember anything after that. I think I must have pissed my pants. Or walked out.

Or pretended it never happened.

Which is what you do when you can’t think of anything else.

My dad was 78 when he died this past Wednesday morning. His death certificate says he went at 1:20 in the morning. It’s an odd hour to die, I guess, as far as those things go. No birds are outside singing. The world is mostly asleep or drunk or watching late night TV. Everything is yawning. Everyone is over it, hanging on by a thread.

And there you are, alone in a hospital room. Even the nurses probably don’t give much of a shit. Nothing against the nurses, but I suspect many of them are numb to it all now. To them, the death of my father in a dimly lit room on some cold winter night in New England, it lacked all the poetry that someone like me might try to assign to it. It’s understandable, of course. People just want to get home to their own beds. To their own sleeping kid’s heads and their own vape pens and their own microwave meatball pies at the end of a long night in SadSickLand.

He had a heart attack it says, on the certificate. He had pneumonia, my mom told me.

I remember once a doctor telling me that pneumonia is an old man’s best friend.

That’s what my mom told me on the phone when she called to tell me he was gone.

I wonder what his death was like though, you know?

Was he hacking so hard that the nurses were raising their eyebrows? Was he fighting to live or was he just over it? Did he say anything/ or try to?

Did he say my brother’s name?

David.

Did he say mine?

Serge.

Or was he, like, thinking those things/ our faces/ our voices/ our breath/ one of us in his arms right after we were born/ so small/ so tiny/ like a medium size bluefish from a party boat in the 70’s. Warm kid, bundled up in the cheap blue blanket, hiccuping sobs as he tries to focus on the giant life wrapping him in its grasp/ the dad brushing his Burt Reynolds porn mustache on the baby’s pink cheek.

The gentle stab of the new pop’s bristles.

The country tones of his Parliament breath.

What did he say when he first held me in his arms? Did he whisper in my ear? Did he say he loved me? Did he tell me it was going to be okay? Or did he not say anything at all because he wasn’t sure about any of this? That he wasn’t sure what was to come?

I wonder if I crossed his mind as he was dying.

I looked up the weather for when he died.

At 12:51am, a half hour before he passed, it was 32F and clear in his part of Massachusetts.

At 2:51am, an hour and change after he’d gone, it was 27F with passing clouds.

Then at, 3:51am, more than two hours after my dad had died far away from me, as I slept in my bed, unaware he was even ill or hospitalized or anything, the weather just outside Lowell General Hospital was 27F with ice fog.

They had probably rolled him out of the room by then, I figure. Out in the hall, slow clacking towards the elevator, like an old train huffing into the station. Then into the bright elevator, a couple of Red Sox lifers, two orderlies in their early 30’s, maybe just one/ I don’t know.

Checking his phone on the way down to the morgue. Checking scores or checking Tinder. Living his life, thinking about food.

My old man under the white sheet, maybe his last currents pinging around up in his head.

The orderly likes a TikTok.

My dad says my name down in that fading dark.

And I appear as ice fog, holding the whole fucking hospital in my arms like a baby.

Pepe was what I called my dad’s dad. I only met him a few times when I was a boy. He was a quiet man with rock chunk hands and his face was hard and pink and he wore something European that smelled like flowers dipped in booze.

He enchanted me simply by existing. His ashy hair and full mustache decorated a face that never spoke a single word I understood except my name, which was also his son’s name. My dad. Born in Belarus, Pepe ended up in Poland, and then on to northern France where my dad was eventually born in 1944, in the month of August, two months after D-Day, as the war raged on across the land.

I remember this the most.

Me, at 8 or 9, in my hip boots, standing in the river quite far from the bank. My dad out of sight, off fishing alone. And Pepe, squatting on the bank behind me, like only foreign men can squat. Like Vietnamese farmers resting in the jungle shade or Russian truckers sharing vodka at the snow squall petrol station, Pepe would rest his haunches on the slight cushion of air space between the backside of his shins and the rear of his hams and hover there, perfectly balanced, in no pain at all, as he rolled on the balls of his coal miner feet and stared at me, out in the swift cold river, without ever looking away.

When a smallmouth bass would slash my spinner I would feel my heart rise up on proud thermals and I would be looking down at myself fighting the fish and watching my grandfather from a distant land- who could not communicate with me except to smile or point or use his fingers to mimic eating food- staring at me/ unemotional/ with intense concentration/ as he smoked his hand-rolled Frenchy cig and saw his blood out in the water holding the bass high for him to see.

He would raise one hand slowly then, and perhaps let me have a slight grin, and I would feel the power of the male figure overcome me with a million trillion years of honor and respect and love and masculinity and acceptance and everything.

Although, he probably was just saying to himself that I was a weak twig who would likely die in the first moments of the next war to come. It doesn’t matter. He could not speak to me. I think that is the secret. Never talk to your grandkids. Simply smile at them, roll a smoke, watch them catch short bass in the creeping river mist.

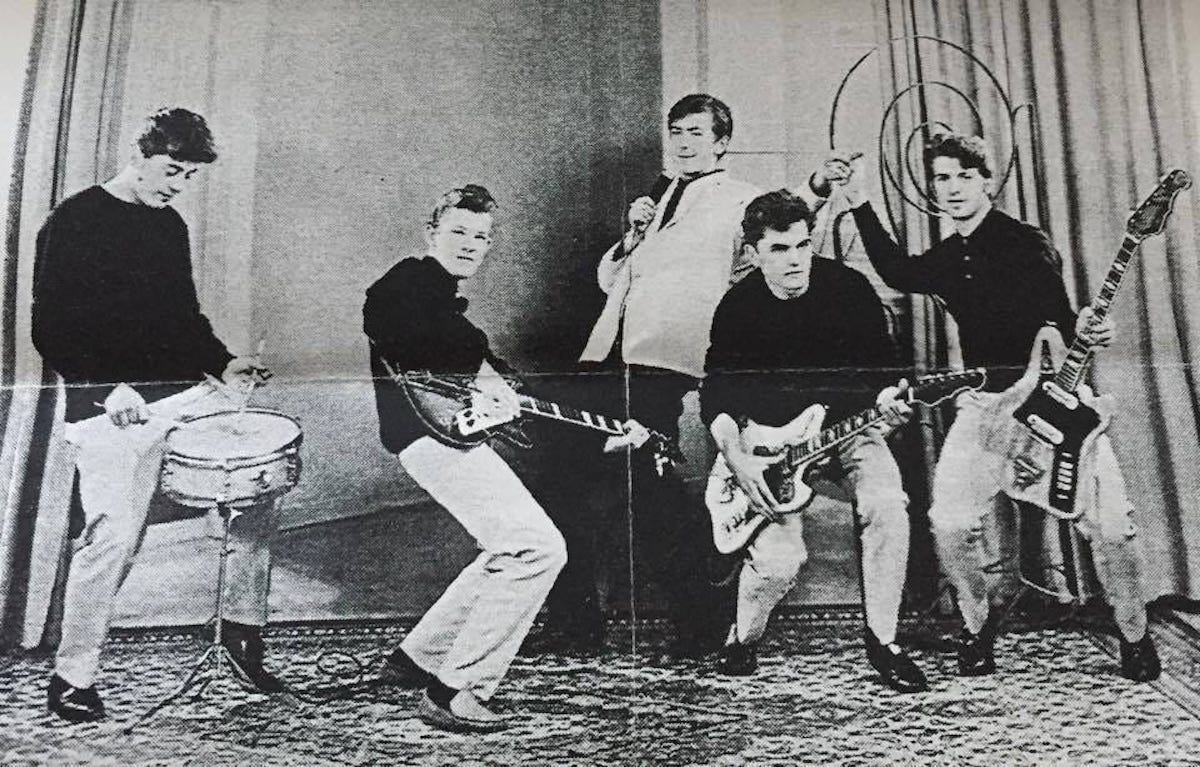

Once at TT the Bears in Cambridge, at a Marah gig, my dad came up on the stage to play the drums with us on a song. It was right when we had reconnected with him at the urging of my mom. We had been on the Conan O’Brien Show performing a song and I think she was proud and wanted, somehow, to show her MIA ex that she had done really well with the two boys he had abandoned. I don’t know. I can’t speak for her, but one call from her one morning while we were out in California touring set the stage for this kind of meeting I had never imagined could happen.

Nor did I ever pine for it or long for the day.

Across every expanse of my mind, he was dead. Gone. Evicted from my spaces and buried under the ruins of a thousand cities I had never known/ rubble I had mined myself just to get the job done/ stones and gravel and dust I had hauled up out of the hole in my Earth to dump upon his eyes and his voice and his charming beer-buzzed smile and his endearing outlaw’s laugh and his sinister drunken machine-gun chuckle and his vicious parts and his anti-American booze-addled rants and his putting a shotgun to my mom’s head and his slapping my ass hard with his wedding ring hand as I fled from him in horror and his buying me brownies and hoagies and cans of Pepsi at 7-11 on fishing mornings and his not answering the door on other fishing mornings and his leaving me hanging, leaving me hanging, leaving me hanging and hurting and hanging and dying and his sense of cocky superiority to other people and his propping me up on the bottoms of his feet as he laid belly-down on the shag rug in the home we had once all shared before things turned for the worse, and letting me sit there as if his legs were the strongest chair in the world/ a chair that moved slowly under my little young ass/ chair letting me wobble and weave up in the air like a tall loose monument bound to come down/ up there in the sky as we watched Porky Pig or Foghorn Leghorn and he laughed so hard and drank beer after beer and I could smell the scalloped potatoes my mom was cooking in the kitchen of the house that was our home.

It was surreal, of course, looking at my Dad, now an older guy in his 60s, frailer than he’d been when I knew him. My brother Dave (our singer) and I: we had not seen him for a long, long time by anyone’s standards. By the time I was 11 and Dave was 9, our Dad was gone. He had simply disappeared and no one seemed to know where to. Or why.

It was assumed he had gone with his girlfriend, Merry, but nothing was ever looked into as far as I could tell. Yet, here we were now, decades having passed, and I felt wildly uneven about everything. For the slim crowd in this squat dark club, this might have been a pretty memorable moment, I guess. Band’s long lost dad joins them onstage to jam. But it all felt heavier than that to me. And the stage was MY place. It was OUR place, me and my brother’s. Filthy loud nightclub stages had become, unintentionally, or at least unknowingly, the few slight sections of the planet that we had been able to claim as our own.

For us, the band was everything. And to stand up on any stage, anywhere, in any club, in any city, on any given night, that was all we had ever wanted. And we had worked so hard to get that. Even if others thought that our level of success was low and we had so far to go to ‘make it’, our thoughts were always: Fuck You. Because this was our realm. This was our galaxy. This was our safe place where we could reveal ourselves honestly and without fear and now here he was, the man who had walked out of our world entirely for over 20 years, coming back to feast, easily, on the fruits of our labor.

It was cool, don’t get me wrong, playing music with my dad for the first time that night. But it was also heartbreaking. Because I found myself crushed by his presence.

I had killed the man.

Now the killed man was back.

And that’s always an awkward situation.

So much of my life I have spent on the run. Not from certain places or the law hunting me down or bad vices all up in my skin. For me, the running has been from the people, a select but powerful few, who have hurt me in the ways that can undo a human spirit to the point of straight-up dying if you let it.

My dad was one of those people. It is with a heavy, heavy heart now that I write about his death. Like many people, I wonder what might have been had circumstances been different with us. But unlike many others, I also continue to feel a profound sense of persistent injury coming from the man. He remains, as he always has, in life or death, a source of colossal pain for me. Which is somewhat embarrassing to me as someone who has been chewed up and spit out by others as well.

The questions circle my head, mountain crows screaming in the morning. The forest shakes. The dew rains down. The world is anything but peaceful now.

Was it me? I ask myself.

The same old question every divorce kid asks themselves, I ask it too.

Was this because of me?

And almost right away I can talk myself out from beneath that weight. I can assure myself, as the memes assure us, that it was not me. That it was not the boy. The child. The innocent chunk of a kid who couldn’t have messed up a father/son thing if he had even wanted to at the ripe old age of fucking 8. Or 10. Or whatever.

But that kind of self-help reassuring comes with a caveat, man, and that caveat is this.

Later, did I drop the ball?

Did I never try hard enough to pull this person back up out of the rubble I had buried him under? I had killed him off in the name of my own battered heart, but then what?

Back on that stage, back under those lights that had become my home, there he was, walking out of the past, smiling, drinking near beer, telling me he loved me after so many nights/ YEARS!/ of letting me know/ clear as day/ that he most certainly did not. In absentia, I had created my own story of my dad and his worth and his cold, cold heart.

Now, looking at him sweating his old man ass off back behind the kit, I felt more confused and lost than I ever had. And I still do. And now I always will. And I feel like punching a hole in the wall right here by my laptop. It isn’t fucking fair. I did not deserve any of this.

If you are thinking to yourself right now that I need to:

– just hand this over to God

– forgive and move on

– try to understand that my dad loved me ‘in his own way’

– realize that so many others have had it much worse than me

– understand that, to you, I seem caught in a loop of sadness/loss/grief/anger/blame/reboot

– or anything like that

…then I don’t know what to tell you, really. These things aren’t something I wrestle with for branding purposes or whatever. I’m not looking to be crowned the #abandonedson Hashtag King or anything like that. I am just really, really struggling with knowing that my own dad never had time for me or for my kids. And that he didn’t fight to win me back. And that he never even felt like there was any REASON for him to even have to try and win me back. He never apologized. He never looked me in the eye and said I fucked up, son. He never showed up at my door crying and begging me to let him try, even in these final years, to redeem himself in the eyes of love. He never did any of that.

Instead, he came around a little, spoke often of what others had done to him to impede his progress in life, and blamed my mom (who even went so far as to try to reconnect him with his sons) for everything that had ever happened in a marriage in which his alcoholism had achieved legendary status even in a town full of hard drinkers and failed dads.

I can’t understand any of it. I cannot understand why some people kept believing in him or wanting to forgive him even when he seemed entirely unwilling to accept even a tiny sliver of the responsibility for leaving two good, lovable sons in the middle of the night. To drive away from them, without a goodbye or anything, as if they were a dead cat he ditched down on some river road.

My guts hanging out my mouth.

My tongue sticking out like an arm.

Don’t leave me, the kid says.

His eyes bulging out of his skull where the tires sent him spinning off into forever.

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin. Once in a blue Muskie Moon, he backs away from the computer, straps on a guitar and plays some rock ’n’ roll with his brother Dave and their bandmates in Marah.