Even in the throes of writer’s block or technical difficulties, I can’t imagine having to be forced to make an album. It’s usually something I get very excited about. But it turns out there are a great many famous albums which the artist would have much rather not done. Sometimes, usually, these are what’s known as “contractual obligation” albums. That means the artist’s contract called for them to make a certain number of recordings in a certain period of time, and they hadn’t met that requirement yet. So, they were forced to come up with something. The results are wildly varied and sometimes surprising.

Even in the throes of writer’s block or technical difficulties, I can’t imagine having to be forced to make an album. It’s usually something I get very excited about. But it turns out there are a great many famous albums which the artist would have much rather not done. Sometimes, usually, these are what’s known as “contractual obligation” albums. That means the artist’s contract called for them to make a certain number of recordings in a certain period of time, and they hadn’t met that requirement yet. So, they were forced to come up with something. The results are wildly varied and sometimes surprising.

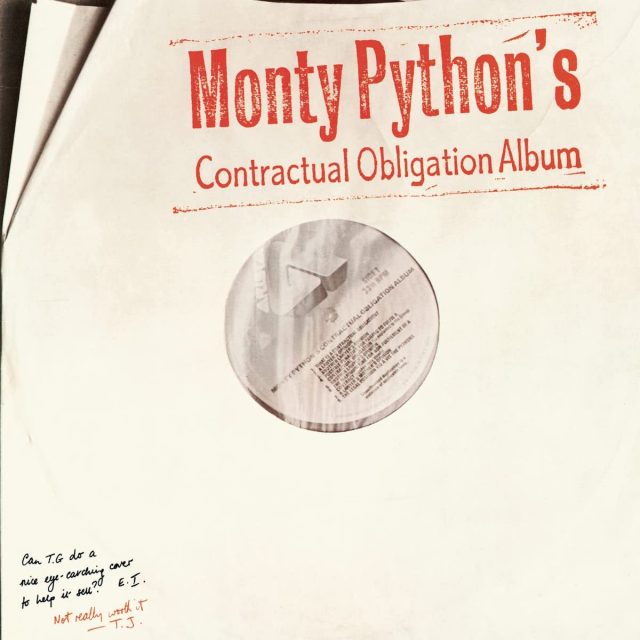

It may be the “contractual obligation” label came about courtesy of Monty Python, who actually called their 1980 record Monty Python’s Contractual Obligation Album.

I do like it when the album titles are cheeky hints at the circumstances. For example, Here, My Dear by the late Marvin Gaye. In 1977, Gaye was failing to pay support to his ex-wife Anna Gordy. So, he was forced by court order to give half the royalties of his next album to her to catch up on the missed payments. He decided to make an awful album and set about doing so in his home studio. But, it wasn’t long before the whole notion began to fascinate him. The uniqueness of the task appealed to his artistry, so Gaye ended up making a very candid and personal breakup album. It was, of course, a commercial flop — but is retrospectively considered a masterpiece.

Maybe not a masterpiece, but it was his last hit record, Todd Rundgren released The Ever Popular Tortured Artist Effect in 1982 so he could get out of his contract with Bearsville Records. He obviously wasn’t taking things seriously, which is evident from the album’s double-entendre single Bang The Drum All Day.

Sometimes the best “contractual obligation” recordings never get released by the intended label. Rather, the label refuses to put them out — ensuring their legend grows over time before they are eventually made available to fans. Such is the case with Cocksucker Blues by The Rolling Stones, who had one more song to deliver to Decca and gave them one laced with expletives:

“Where can I get my cock sucked?

Where can I get my ass fucked?”

Decca opted not to release it as a single and the Stones were free to start their own label.

If you think that’s epic, the Stones have nothing on Van Morrison, who needed to record 36 songs to get out of his contract with Bang Records in 1967 before he could go record Astral Weeks for Warner Brothers. Morrison did all the songs in a single session, on an out-of-tune guitar — making stuff up as he went along. Rather than brown-eyed girls, he did one-minute jams of songs about ringworm, royalties and whether he should eat a Danish or a sandwich:

John Lennon had to put out his 1975 Rock ‘N’ Roll album of classic covers to generate royalty income after being found guilty of plagiarizing Chuck Berry’s You Can’t Catch Me with Come Together. But Lennon seemed to enjoy the experience — his last studio album for five years.

Neil Young went through a very drawn-out “let me out” affair with Geffen Records, practically from the moment he was signed. His first album for the label, after years with Reprise, was 1982’s Trans. The album was a huge change of direction — loads of synth and Vocoder as Young set out to make something of a concept album inspired by his struggle to communicate with his disabled son.

It sold better than anything he’d done in recent years, but the label sued him for making music that wasn’t Neil Young enough. They told him to make a rock album. But, he had a country album ready to go, so he shelved that and made a rockabilly album. Geffen wasn’t impressed with Everybody’s Rockin’ by Neil Young & The Shocking Pinks. The artist was making a point — “don’t tell me what to do!” But that’s not to say the album is bad. Like Trans, it’s quite awesome, especially Wonderin’.

Next, Young put out Old Ways, that country album he had ready, and then the undefinable Landing On Water — my two least favourite of the Geffen years. His swan song on the label came in 1987 with — finally — something approaching what they wanted all along, a Neil Young & Crazy Horse record. Life isn’t a great album, really, but I remember it making an impression when it came out. We were way more interested in the next record — his return to Reprise. Neil Young & The Blue Notes’ This Note’s For You was pretty great.

The moral of the story: Don’t try to control Neil Young — and be careful what you wish for when you try to pin down his contractual obligations.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.