I wrote this feature about Doors singer Jim Morrison on the 40th anniversary of his 1971 death. I was fortunate enough to talk to two of his surviving bandmates, along with old friends like Alice Cooper, artists he influenced like Burton Cummings and Ian Astbury, and famous fans and followers like Michael Bolton and ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic. This seems like a good day to reprint it. Feel free to listen to your favourite Doors cuts while you read.

For Doors fans, July 3 marks the anniversary of Jim Morrison’s untimely death in 1971 — a day to remember his life, his music, his poetry.

For drummer John Densmore, it is perhaps a date best forgotten. And he has. “What is it, July 3?” asks the veteran percussionist. “You see, I don’t even know the date. I prefer to celebrate Dec. 8, his birthday. After all, Jim died at 27 because of alcoholism. I don’t want to glamorize that. But I am real proud of Jim’s music and poetry. My anger over his demise is gone. I have a deeper respect now than I did before for his vision, for what he was trying to do. He was trying to make some deep changes.”

On a musical level, he succeeded. “Morrison took it to a different place completely,” says singer Burton Cummings. “He opened my eyes to the fact that lyrics could go anywhere, could be dangerous and dark.” Cult vocalist Ian Astbury — who has sung with the surviving Doors — agrees: “The first time I heard The Doors in 1971 at age 10, all of a sudden there was a different animal in the room. This wasn’t pop. This was something else — almost scary.” Even Michael Bolton is a fan: “He was a one-of-a-kind writer and artist.” The bottom line, says Doors guitarist Robby Krieger: “He was different than anybody I’d ever met. And I’ve never met anybody like him again.”

James Douglas Morrison met the world in Florida in 1943. His father was a career naval officer and future rear admiral. The family moved frequently. The elder Morrison dressed down his children like sailors for their failings. The seeds of Jim’s rebellion were home-grown and planted early. “That’s the whole story right there,” says Astbury, who met Morrison’s family. “The Oedipus complex, The End, the Morrison mythology. It all comes from the dynamic with The Admiral.”

By the mid-’60s, Morrison was estranged from his family. He would later claim to be an orphan. He studied English, film and theatre at UCLA. His classmate: A keyboardist named Ray Manzarek. After graduation in ’65, they met on Venice Beach. Morrison had been writing poetry; he recited Moonlight Drive. Manzarek heard great lyrics and suggested they form a band. They enlisted Densmore and Krieger, took their name from an Aldous Huxley novel and The Doors were born.

They spent two years in L.A. clubs like the Whiskey a Go Go honing their sound: A psychedelic cocktail of Manzarek’s classical chops, Densmore’s jazz grooves and Krieger’s flamenco licks, centred around Jim’s dark croon and shamanic intensity (at times, he claimed to be possessed by a Native American killed in a car wreck his family passed on the road).

In 1967, they released their self-titled debut LP. The Admiral heard it and wrote him, suggesting he quit music for lack of talent. Others disagreed. The single Light My Fire ignited a four-year whirlwind that produced six albums and multiple hits including People Are Strange, Hello I Love You, Roadhouse Blues and Riders on the Storm. “During those years, all we did was write music, record music and tour,” says Densmore. “We were trying to create movies for your ears.”

Fame and fortune did not tame Morrison any more than his father’s discipline had. He infuriated Ed Sullivan by singing the word “higher” on live TV. He trashed a recording studio. He tangled with cops. His substance abuse increased. He literally walked on the edge. “Jim and I used to drink a little together,” understates Alice Cooper. “People tell me stories I barely remember — like us both hanging off of a balcony to see which one could hold on longest. That was Jim — he didn’t mind balancing on a building 6,000 feet up drunk. I can tell you 20 times he could have died.”

Cummings may have witnessed one. On his first night in L.A. the Guess Who frontman ended up driving a drunken Morrison around after a party. “He drank like a condemned man whose last meal was beer,” recalls Cummings. “He was far too drunk to drive. So I volunteered, and we drove all night as he talked about Renaissance painters and great poets and writers and the universe and relativity. He was a brilliant thinker, but no good at self-preservation.”

By 1969, the cracks were showing. He was late for concerts, drunk in the studio. The final straw came after a crazed show in Miami: Jim was charged with exposing himself onstage. Despite zero proof and even a letter of support from The Admiral, Jim got six months in jail. He never did the time, but the damage was done.

“We were banned everywhere,” recalls Densmore. “We couldn’t get any gigs for a year. Personally, I was relieved because I knew Jim had a major problem.” But in the era before rehab, no one knew how to solve it, says Krieger. “We actually did try to do an intervention on him at one point, but it didn’t work. He was just not the kind of guy that it would have worked on.”

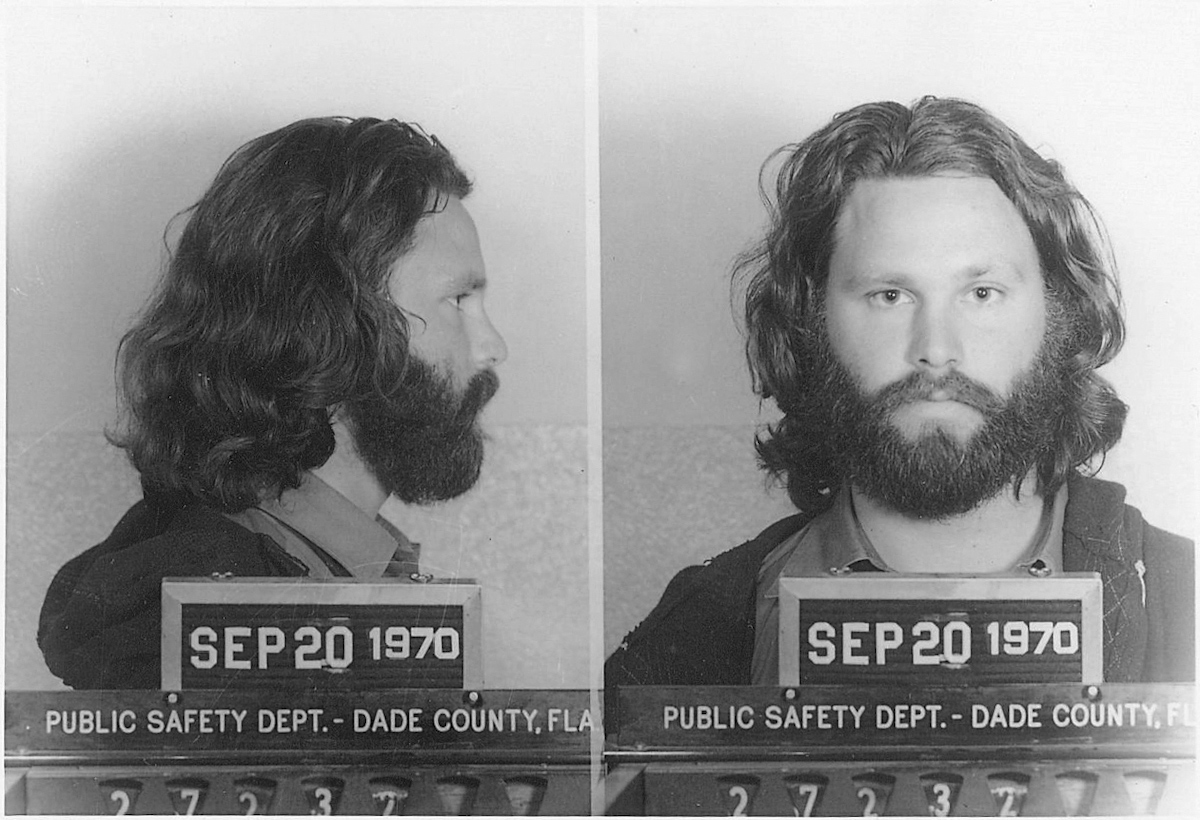

There were more albums and tours, but the band never fully recovered. Jim gained weight and grew a beard. After he melted down onstage in New Orleans, The Doors quit the road and hit the studio for what would be their final (and according to Densmore, finest) album, L.A. Woman. When it was done, Jim went to Paris with girlfriend Pamela Courson for an extended holiday. He never returned. On July 3, he was found dead in the bath. It’s said he ODed on heroin. No autopsy was done; heart failure was his official cause of death. He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery; his headstone bears a Greek inscription that means, “True to his own spirit.”

The surviving Doors made two more albums, but by 1973 they were done. History wasn’t through with Morrison, though. In 1979, The End was used in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (“When I saw that,” recalls Astbury, “it was like a religious experience”). In 1980, manager Danny Sugerman published the biography No One Here Gets Out Alive. A new generation discovered him. By 1981, Morrison was on the cover of Rolling Stone, beside the headline: “He’s hot, he’s sexy and he’s dead.”

Since then, Morrison’s impact on music and pop culture has only grown. His baritone echoes in countless artists, from punk godfather Iggy Pop to Joy Division’s Ian Curtis to Tea Party frontman Jeff Martin. His story has been told in Oliver Stone’s polarizing biopic The Doors and the Grammy-winning documentary When You’re Strange. Fans make pilgrimages to his grave. He was eventually pardoned for whatever went down in Miami. Even ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic has paid homage to Morrison on the video for Craigslist. “He is so iconic,” says Yankovic, who lost 27 pounds to fit into Jim’s leather pants. “His personality and charisma were undeniable. He was bigger than life.”

That may have been part of the problem, suggests Cummings. “The shaman, Light My Fire, leather-clad guy — I think he was trapped inside that image. He wanted to be Rimbaud, but fans wanted him to be the gorgeous Lizard King. It’s a shame.”

Astbury sums it up: “If he had looked like Van Morrison, things might have been different.”