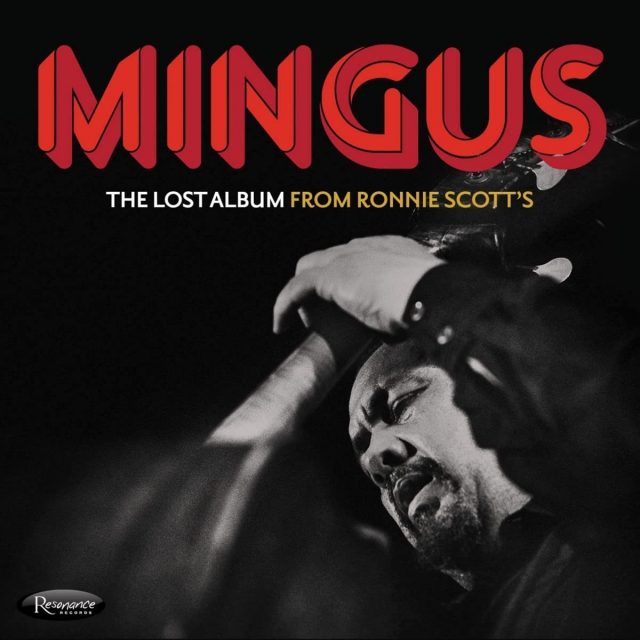

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “The Lost Album From Ronnie Scott’s is a volcanic, never-before-heard 1972 club performance by bassist-composer Charles Mingus’s powerful sextet.

The live set, comprising nearly two-and-a-half hours of music, was professionally recorded on eight-track tapes via a mobile recording truck on Aug. 14-15, 1972. However, the performance went unreleased, for Mingus — along with every other top jazz musician on the Columbia roster except for Miles Davis — was dropped by the label in the spring of 1973.

Resonance co-president Zev Feldman, who co-produced the Scott’s material for release with David Weiss, says, “This is a lost chapter in Mingus’s history, originally intended to be an official album release by Mingus that never materialized. Now, we’re thrilled to be able to bring this recording to light for the whole world to hear in all its musical and sonic glory. It’s especially exciting to be celebrating Mingus with this release in his centennial year.”

A statement in the Resonance collection from Jazz Workshop says, “In Sue Mingus’s memoir Tonight at Noon, she recalls receiving the extraordinary tapes [the band] had recorded; the reels remained in the Mingus vault, untouched until now. It is our honor, 49 years later, to present, with Resonance Records, this historic performance.”

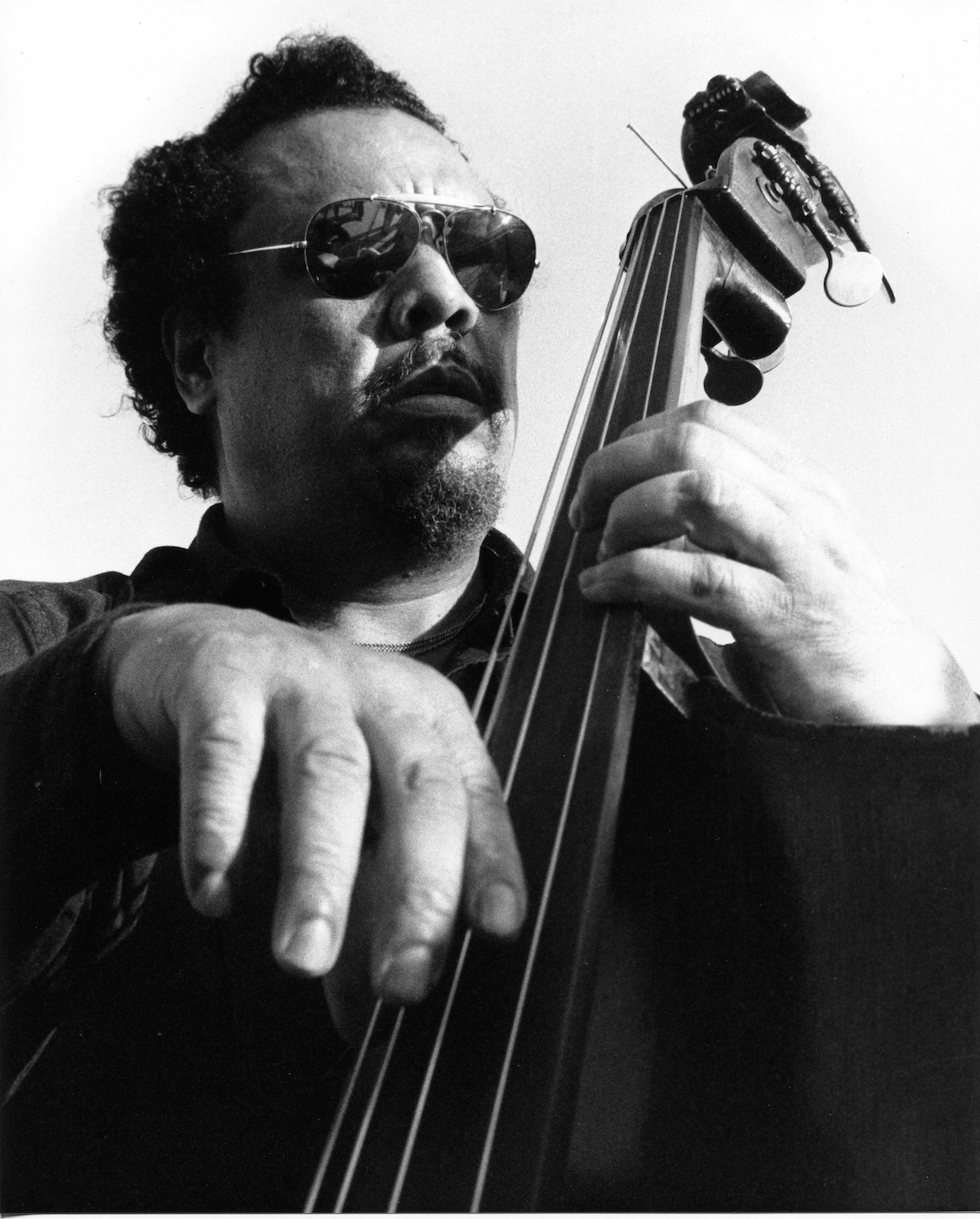

In his knowledgeable overview of Mingus’s activities of the early ’70s and his stand at Scott’s club, British jazz critic and historian Brian Priestley, who penned an authoritative 1983 biography of the musician, writes, “The magnificent music contained herein comes from a special period in the life of Charles Mingus, one in which he re-emerged from the depths of depression and inactivity, to be ultimately greeted with far wider acclaim than he had ever previously experienced.”

By the time Mingus’ band took the stage at saxophonist Scott’s celebrated London club, the great jazz man was experiencing a career renaissance: He had received a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and seen his music adapted for choreographer Alvin Ailey’s The Mingus Dances in 1971, while 1972 saw the release of his potent autobiography Beneath the Underdog and his widely acclaimed big band album Let My Children Hear Music.

Though his group still featured the formidable saxophonists Bobby Jones (tenor) and Charles McPherson (alto), the sextet was in a state of flux, but the new members delivered on stage. Pianist Jaki Byard was succeeded by the relatively unknown John Foster, who showed off both his keyboard and vocal chops at Scott’s. Longtime drummer Danny Richmond, who had joined the pop band Mark-Almond, was replaced by the ingenious, powerful Detroit musician Roy Brooks, who demonstrated his invention the “breath-a-tone,” which allowed him to control the pitch of his kit while playing, and, on a couple of numbers, his abilities on the musical saw. The trumpet chair was filled by the phenomenal 19-year old Jon Faddis, a protégé and acolyte of Dizzy Gillespie.

The Lost Album features nine performances captured during the two-night engagement; some of them — the then-new compositions Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues and Mind-Readers’ Convention in Milano and the warhorse Fables of Faubus — are epics that stretch close to or past the half-hour mark. In its entirety, the set bears comparison to Mingus’s storied concerts at Monterey, Carnegie Hall and Antibes.

During the English engagement, which came at the end of a European tour, Priestley conducted a joint interview with Mingus and McPherson at the club. He found the bassist in a philosophical mood: “Life has many changes. Tomorrow it may rain. And it’s supposed to be sunshine because it’s summertime, but God’s got a funny soul. He plays like Charlie Parker. He may run some thunder on you. He may take the sun up and put it in the nighttime, the way it looks to me.”

In a new interview with Feldman, McPherson deftly characterizes his longtime employer’s musical approach: “[Mingus] liked for his music to be clean enough for it to be obvious that this is worked out and thought out, but not so pristine that it sounded robotic or unanimated or not human — too processed. I think ‘organized chaos’ is an apt term because that’s the way Mingus’s music really did sound; it did have almost this free-wheeling kind of a vibe and yet, you can tell it’s written out, it’s thought about, and it has all the elements of organization, but still, it has the elements of spontaneity.”

A pair of jazz’s most celebrated bassists offer their appreciation for Mingus in interviews conducted by Feldman. Christian McBride says, “Mingus just has such an individual sound, such a presence. He had some real estate that no one else had. I love how Mingus’s music is this very blurry balance of blues, swing and the avant-garde … He did it in a way that no one else did.” Eddie Gomez notes, “He was this big influence in a big forest, so I assumed that he got a lot of recognition. Maybe he should have gotten more. He’s still one of the great influences in jazz music.”

The full measure of the jazz artist’s larger-than-life personality is captured in reminiscences by Sue Graham Mingus (in an excerpt from her 2002 book Tonight at Noon: A Love Story) and Mary Scott (in a new interview with Feldman) of the bandleader and the club owner who were their respective spouses. A rich and very funny recollection of the mercurial titan is offered in Feldman’s interview with New York writer, raconteur, and woman-about-town Fran Lebowitz, who knew both the Minguses well. She recalls one encounter in which an angry Mingus chased her out of the Village Vanguard and through Lower Manhattan.

She says, “We went down Seventh Avenue really far; my recollection is to Canal Street. We ran to Canal Street and I couldn’t run anymore. I was like 21 years old. I don’t know how old Charles was. He was probably in his late 40s at least and he was not exactly in Olympic condition. Neither was I, but compared to Charles I was. I just fell on the ground. I couldn’t run anymore. And then when he reached me, he fell on the ground and he’s panting. And then he just looked at me and said, ‘You want to go eat?’ because I guess he realized we were near Chinatown where he was the star eater of all time.”

“Music is my life. Without it I’d be dead. All I need is score paper and a piano.” — Charles Mingus, from an interview in London, 1972.”