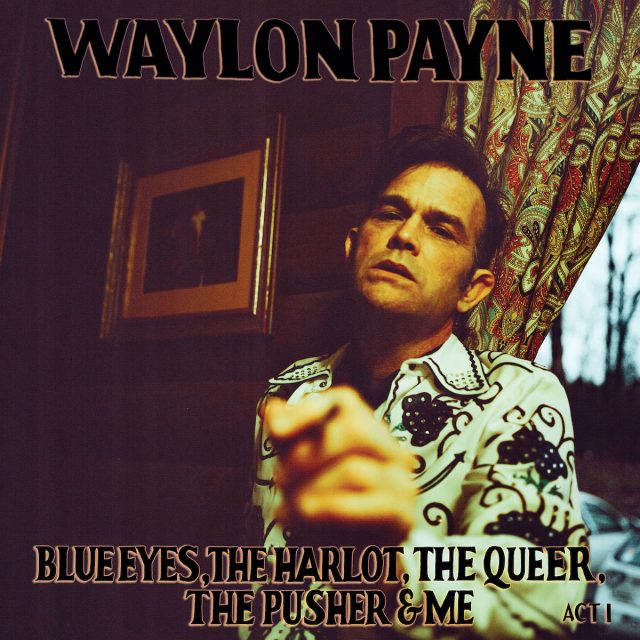

THE PRESS RELEASE: “Magic happens when everything comes together like it’s supposed to — when the joys and the pain, the triumphs and the missteps all click into place to be seen for what they truly are. Waylon Payne’s Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me is such a moment, the culmination of an extraordinary journey set to music.

“A son of country music royalty, a teenaged Baptist preacher turned addict and actor, Payne sings about fathers and sons, faith and addiction, recovery and renewal with devastating clarity. His character-rich collection harks back to a way of telling stories in song that revealed kept secrets and promised mystery. Over his years, Payne has felt the terrible power secrets can hold and learned the transformative value of releasing them. Finally, he’s in a place where he can harness that power to create transcendent work.

“Payne recorded Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me primarily at Southern Ground Nashville, a converted century-old church building just off Music Row that once housed Monument Studios. Payne’s mother, country singer Sammi Smith, cut her iconic version of Kris Kristofferson’s Help Me Make It Through the Night at Monument. When Payne recorded his vocals, he says, “I stood in the same spot she stood and sang while she was pregnant with me.”

“To help realize his musical vision, Payne worked with producers Eric Masse (Miranda Lambert, Rayland Baxter, Robert Ellis) and Frank Liddell (Lambert, Lee Ann Womack, Chris Knight) to assemble a group of musicians that spanned both genres and generations. In addition to highly regarded players like bassist Glenn Worf; guitarists Jedd Hughes, Ethan Ballinger, and Kris Donegan; and drummer Blake Oswald, the team brought in Cage the Elephant guitarist Nick Bockrath, as well as Mickey Raphael, Willie Nelson’s longtime harmonica player and a former band mate of Payne’s father, Jody Payne. Jerry Roe, like Payne a second-generation music man whose father spent years working for Johnny Cash, played both bass and drums. Other musicians on the album include longtime guitar player and friend Dean Person, slide guitarist Harrison Whitford, and violist Kristin Wilkinson, who arranged and conducted all the strings.

“As a result, Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me sounds both timeless and out of time. It exists in music’s liminal spaces, the way the late ’60s and early ’70s albums of Kris Kristofferson and Bobbie Gentry did in their day. “Bobbie’s my songwriting hero, the reason I do what I do — her and Kris,” Payne says. “When my family threw me out, I picked the toughest motherfucker I could think of and modeled myself after him. I learned how to be a man watching Kristofferson.”

“Like those artists, Payne draws from tradition while stretching beyond any notions of the mainstream, ultimately standing apart from everything else. Payne has come a long way from the first time he and Liddell met back in the ’90s when Liddell worked for Decca Records. Payne showed up at Liddell’s office, unannounced, declaring his intentions to become a country star. It was the same sort of bold approach Tammy Wynette had made walking in on Billy Sherrill about a block away and 30 years before, and, like Wynette, Payne hadn’t brought any songs to bolster his case. Still, Liddell found Payne’s combination of raw talent, personal magnetism, and determination compelling, even if it still needed to be focused.

“Payne eventually figured out how to harness those abilities, releasing his first album and launching an acting career that included portraying Jerry Lee Lewis in the 2005 Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line and Nashville guitar legend Hank Garland in 2008’s Crazy. At the same time his career seemed to be coming together, though, a drug problem that had started in his teens was developing to a full-blown meth addiction that was ripping Payne’s life apart. “I was acting like a spoiled rock star,” he says. “By the time I started making movies, my ego was a little out there. Then you add meth to that, and you turn psychotic without realizing it.”

“Now eight years clean, Payne finally can put all the elements of his life in their proper place. Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me testifies to a decade-long journey, capturing songs and moments from his most troubled time, as well as the grace and the relationships that led him out of it. There’s tenderness to these songs, an empathy for lost souls who may or may not find their way home. Payne wrestles with the legacy of family dysfunctions in songs like Sins of the Father and What A High Horse. A pair of poignant vignettes, Shiver and Old Blue Eyes, team with tragedy and chilling beauty. “There are jewels buried deep in the record, and if you’re a junkie, you’ll catch them,” Payne says. He views Dangerous Criminal as his point of reckoning. “It’s basically me admitting I have a problem,” he says. “I am a person who will get himself into trouble and in danger unless I keep myself in check.”

“After the Storm and Precious Thing play like prayers, while Santa Ana was written as a lullaby for the young boy whose voice is the first thing heard on the album, a child Payne views as almost a son and by whose first birthday he marks his sobriety. Payne also recorded his own version of All the Trouble, the Grammy-nominated song he wrote with Lee Ann Womack and Adam Wright and which Womack recorded for her 2017 album The Lonely, The Lonesome & The Gone. Payne’s talent as a songwriter has also been recognized by artists Ashely Monroe, Miranda Lambert and Wade Bowen, who have chosen to record his songs.

“Payne may have recorded Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me in Nashville, but it started a decade ago in Texas, as he came through the worst of his addiction and got clean with the help of family and friends there. “For a while, I couldn’t even write,” he says. “I couldn’t put thoughts together, because I had really fried my brain. Once I got sober, everything came.”

“For Payne, each song reflects a different situation in his life. Together, though, they tell of a prodigal son returning home — not to the family of his birth, but home to the true self he’d once nearly abandoned. “The essential DNA elements of this record are my self-written confessions and pleas for forgiveness,” he says. “It all revolves around me getting right with myself and the universe. Maybe I still am a preacher in a way — I just channel into what’s supposed to be.”