“There is no king who has not had a slave among his ancestors, and no slave who has not had a king among his.” — Helen Keller

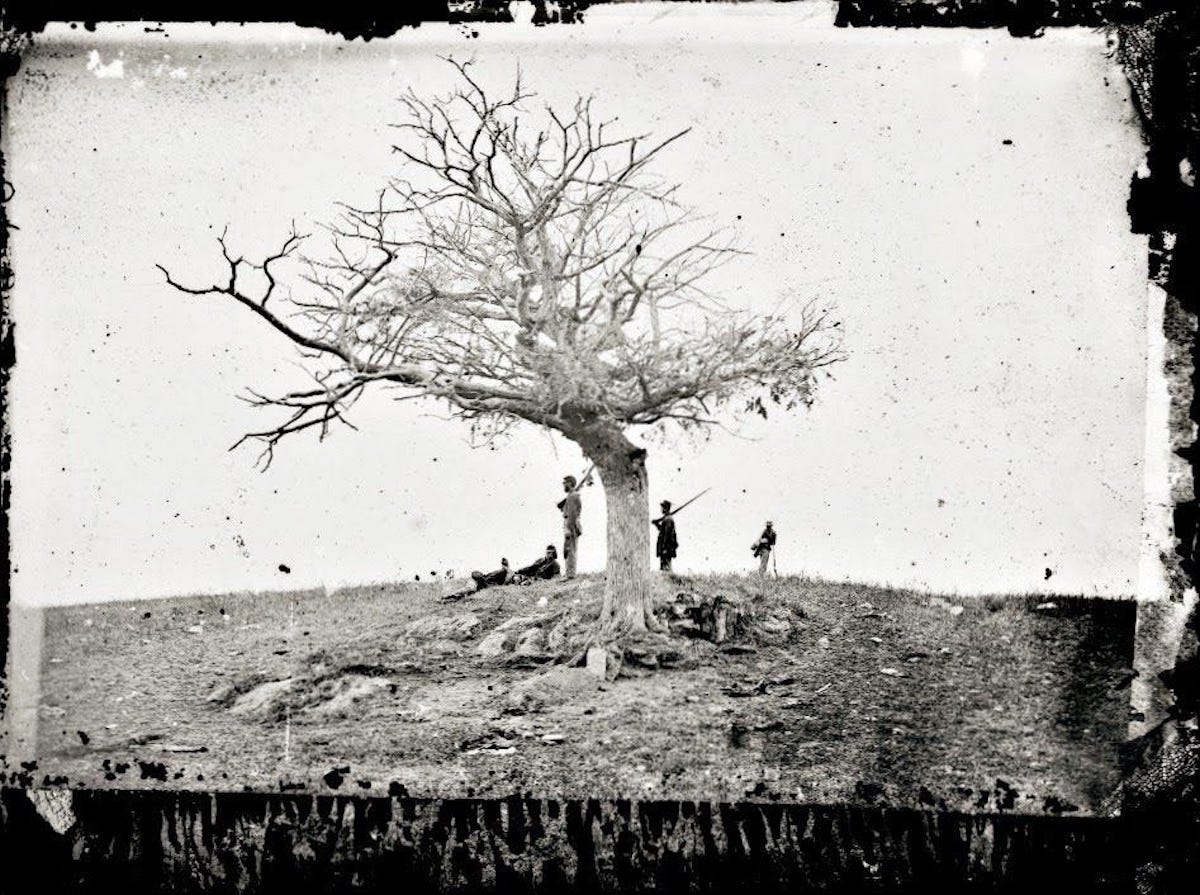

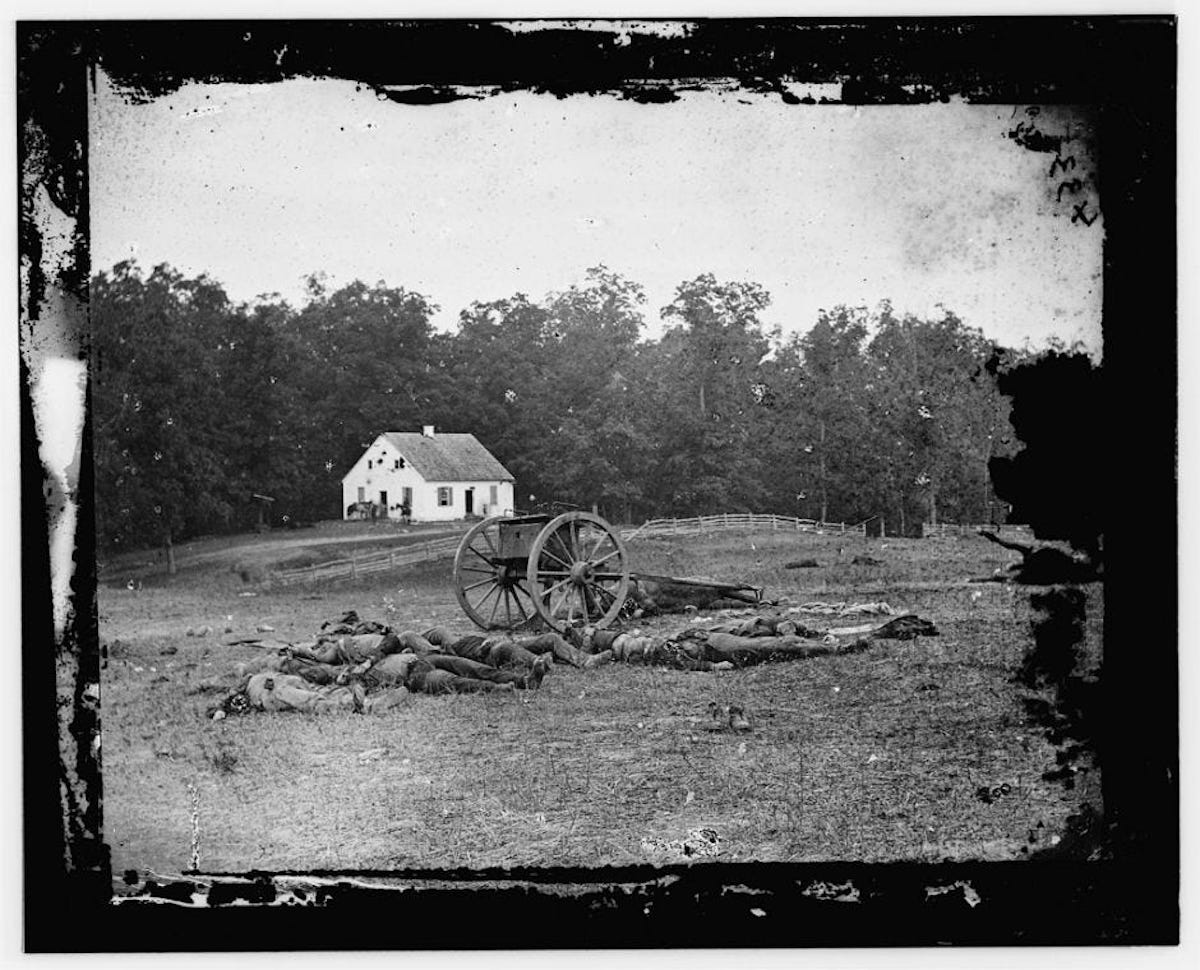

In the woods by the small Dunker Church they had ended up stranded and unconnected. The line that they had moved with, out through the dewy fields of that early September morning, it had been hacked at hard by the enemy. Wavering and loosening, the regiment had somehow gathered the kind of steam not necessarily desired in the midst of battle. But that is the way these things sometimes come down. We can close our eyes and try to see the now: Union boys, slathered in the thick of it/ steaming like a piqued bull/ working with the unnatural swiftness of some sidewinder snake out there in the slick grass. The whole horrifying scene a concurrent face full of everything at once. More than we can ever know.

In the woods by the small Dunker Church they had ended up stranded and unconnected. The line that they had moved with, out through the dewy fields of that early September morning, it had been hacked at hard by the enemy. Wavering and loosening, the regiment had somehow gathered the kind of steam not necessarily desired in the midst of battle. But that is the way these things sometimes come down. We can close our eyes and try to see the now: Union boys, slathered in the thick of it/ steaming like a piqued bull/ working with the unnatural swiftness of some sidewinder snake out there in the slick grass. The whole horrifying scene a concurrent face full of everything at once. More than we can ever know.

Oh, my man:

The chaos in the acrid smoke.

The hollering of unseen men not far away.

The whistling of the balls and the unnerving POOM… POOM… POOM… of the big guns opening back in the farm lots to your rear. Other guns starting in from way out in your front somewhere, and they drop their heat down in your crowd. Taking bones and twisting them out of the skin of a man. Showing his insides, pinching his face into the kind of tight disbelief that comes with a sudden kind of death. Chips of brain on your coat, glistening violet slugs that appear in dark magical puffs, and holding your breath is all you can do/ all I can do/ but damn, what I would give to run out of this whole mess now. To hell with the cause. To hell with any of it. Who wants to die this morning? Not me.

Not us, I’m figuring.

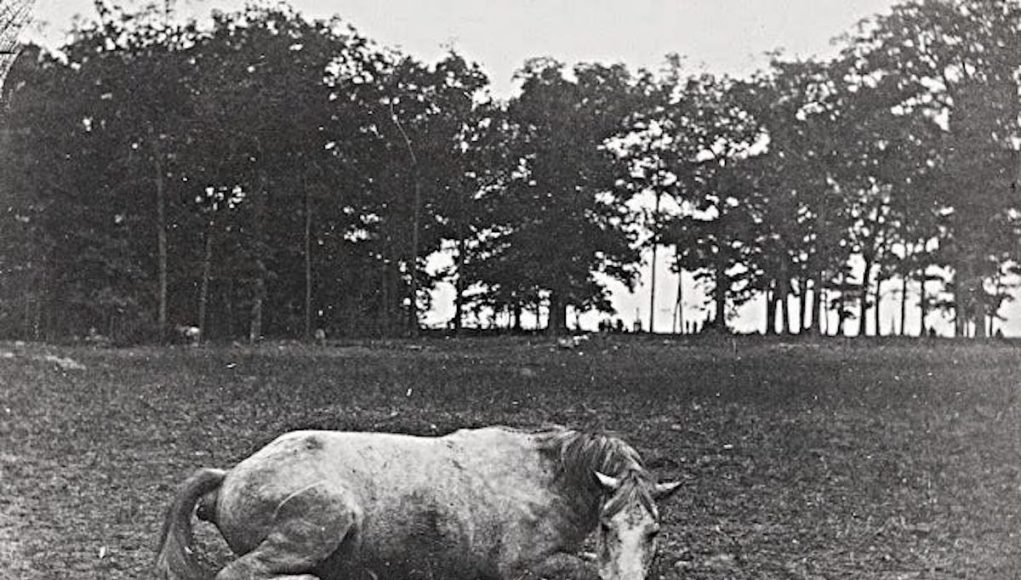

Ah, but you see: sweet impetuosity rules the day. Thus what had begun, well, it had to play out, didn’t it? And so the madness of the moment had swept them up and there was no turning back at that point. On that Maryland field that morning, like so many fields past and so many still yet to come, even to drop down and play dead wouldn’t have likely saved your soldier. Something at some point would probably have slammed into him and it’s all too much to understand. Still, I mean, some errant shell hammering the earth a few feet from his skull, sending the farmer’s dirt into his brains and spilling his brains out onto the land. Or some panicked colonel’s freaking out horse bashing a hoof right through this balled-up fellow’s temple. The din of war silence so we can hear, just for an instant, the lonesome sound of the faint crackling of a Pennsylvania kid’s head popping open.

_____

Sigh.

I don’t know.

How the hell do I know?

How the hell does anyone?

The flashes of consciousness/ the scent of total fear/ the taste of plunging into certain mortal pools/ the all-encompassing totality of being a Civil War soldier in a Civil Battle once upon a time/ it would all come and go rather quickly, I imagine, and yet would remain for each survivor- in dream and in nightmare- for the rest of their lives.

Some would attempt to drink it away. Others would beat it with a vengeance into the puffed ears of their tired wives or into the clenched jaws of their still young, weak sons. Many would tuck it down into their macho chests and march around like real men of the town, all civil and respected.

But nevertheless, for the Antietam boys, it surely remained.

The memory of that morning.

And for the men of the 125th Pennsylvania who survived Antietam, they were probably always trapped out next to the woods by the little country church. Standing in the church or walking down the lane/ eating a ham sandwich in a tavern or trying to take an outhouse piss on a dark cold Christmas morning beneath a sprawling cathedral ceiling of stars/ standing there all alone, one more time, and sensing it all again: the crashing down storm of the energy fear. The metallic taste of a single moment from the past/ when clarity had happened in the middle of fog/ before any help had caught up. That understanding then, that the goddamn Rebels were closing in on their front, and then on their flank, and by the time one soldier realized it all the men around him were doomed. Old friends taking lead in the eye or in the side of the neck. Or in the groin, with a scream, down he went, the blood flowing purple as it slipped down below the surface of all that campfire coffee and all of those letters home.

Like wasps, the shots hissed by and I try to fathom that particular moment but I never really can. No one can. No one will ever know any of it for sure again. These days the old Civil War is merely a strangely comfortable daydream for all of us who ponder it but never knew it at all. An era, true, but more than that is lost, I’d say. With the passing of time we lose the people. And with the passing of the people, we lose the acorns rolling around in our palms/ the old fingers pointing at the sky/ a series of a hundred trillion minuscule moments that together told the only possible tale, they all faded away into basic oblivion when the last veteran took his last breath and died.

Son of a bitch.

It isn’t fair.

Then again, it’s kind of beautiful, ain’t it? The ownership of the shots and the scared and the shaking and the hissing and the pissing in their pants and the vulgarity of the horrifying instants with the bone chips and the intestines on the dirt/ and the crying farm boy with no arm standing there in the smoke/ smiling for a second/ then melting into memory like pines on fire. He knew what he saw, the old soldier did. He knew what he fuck he saw that morning.

But now, it goes. The last Antietam fellow is vacant rattling breath, his back on the bed, cloudy eyes failing to focus. His one granddaughter trying hard, putting a little water on his old chappy lips, but it just runs down his cheek, fresh narrow streams flooding down the ancient hillsides, trickling down his gray stubbly chin and pooling up in shallow puddles in the folds of his wrinkled neck.

Cool well water heading down into the collar of his oniony night shirt as he drags the hazy battle off the surface of this planet once and for all.

At times, and I still can’t believe any of this, but at times when I lay down on the bed, on top of the blankets, my work boots dirty with cut grass clippings and flecks of dog shit or whatever other stuff I’ve been moving through out there in the world (but I plop them up anyways), I stare into the ceiling tiles and I tell myself that her people were there. Her 3x great grandfather, Private David Deviney (or Devinney, depending on which way the old winds blew), he was there.

There as in he fought at the Battle of Antietam/ the ‘Bloodiest Single Day in American History’, where 23,000 men were killed or wounded on that rural Maryland ground across just one September’s day. Private David Porter Deviney, 22 years old, 125th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Company I.

He was there. And you know what? If you ask me, then that means she was there too. At least in my mind it does. In a strange but obvious way.

Ha.

How beautiful is that?

Arle at Antietam.

In the mystical way, hoss.

In the ways of new blood stretching back.

_____

Mother of god, I remember thinking to myself.

Mother of god, I remember saying out loud.

Antietam.

Mother of fucking god.

He was there. He was there. He was there.

The mad adventure of a young man’s lifetime. The relentless marching of war. The loneliness and the struggle. The lingering deep blues and the flash fire memories that remained forever hard to process. The death. So much death. So much terror. So much boredom. So much homesickness. Hardly ever any women. Hardly ever any kisses. Years going without. Years walking into the end. Or not. You could never be sure.

So many questions.

Hardly any answers.

A glimpse of grand generals.

The beating down sun.

Old newspapers smeared with other soldier’s sweat.

The Emancipation Proclamation whispered on a wind.

Hard tack dipped in hot bitter coffee.

Tiny delicate snowflakes on the face of a stiff dead horse.

Whiskey numb Christmas Eve lips.

Guns going off in your ear.

In the night.

In your dreams.

And in the morning.

In your face.

Arle and her grandfather.

They were there.

There, they were.

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin. Once in a blue Muskie Moon, he backs away from the computer, straps on a guitar and plays some rock ’n’ roll with his brother Dave and their bandmates in Marah.