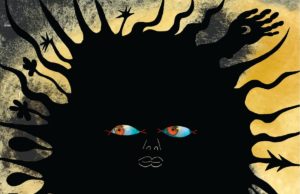

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “In the humid foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, a lover cracks an egg against a china rim and searches its gloss for meaning. Clocks tick in reverse; phones ring out unanswered; Trojan horses arrive at the gates of the human heart and debts are repaid in gold dental fillings. Red-leather-clad and pitchfork-wielding in a playful nod to Grant Wood’s celebrated painting of 1930, Mattiel’s Atina Mattiel Brown and Jonah Swilley proffer songs which ponder the American everyday of the 2020s, teeth to the flesh of a tender Georgia peach as they serve up an album tasting more like home than ever before.

Georgia Gothic, a magic third in Mattiel’s run of albums, was shaped in the quiet seclusion of a woodland cabin in the north of the Atlanta duo’s mother state — “Some faraway place that just Jonah and I could go where there would be no distractions, nothing else going on, and we could turn everything off and only focus on writing songs”, reflects Brown. Where 2017’s self-titled debut and its 2019 followup Satis Factory were written with what Swilley refers to as a “hands-off” approach — he arranging the music and Brown the lyrics and vocals, the two working largely separately — the making of Georgia Gothic was, for the first time, a truly collaborative undertaking. “This was the first time we made a point to just be together and work out ideas in the same room. That was the initial intention … it was about learning what each other wanted to accomplish on a sonic level, and then just trying different things out” Swilley continues. “Everything happened backwards. Normally, you’d have friends that make a band … with us, we started making music from the jump, and then became homies.”

Cultivated by time spent together on the road touring the first two albums, it is this newfound sense of intimacy between Mattiel’s members that enabled the writing of Georgia Gothic not as two separate musicians, but rather as one creative entity. In the cabin, with all the time in the world at their disposal — and entirely away from the usual writing constraints of outside eyes, ears and purse strings — it took almost none at all to lay down an album’s worth of tracks. “I don’t think we really knew going into it whether or not we were going to walk away with a record, or however many songs would materialise, but we ended up recording demos for about 10 songs after a week I think,” says Brown. “It’s kind of a testament to what we can do together as a duo.” The album remained within the four walls of Brown and Swilley’s private world for much of its evolution — with recording taking place in a simple studio set up by the pair in the borrowed room of a dialysis centre, Swilley in the producer’s seat — until, nearing completion, it was transferred into the trusted hands of the Grammy-winning John Congleton (whose extensive list of credits includes artists as diverse as Angel Olsen, Earl Sweatshirt, Erykah Badu and Sleater-Kinney) for mixing.

Not only does the affinity between its creators translate into an electric synergy between Georgia Gothic’s words and music — the brine-shock of Brown’s taut lyricism cut against the bourbon-smoothness of Swilley’s instrumentation — but here too are the palpable spoils of experimentation, each party trustful enough of the other to trial and error their practices into new geometries. Brown’s vocals, for example, shapeshift between tracks: the softly luminous harmonies of album opener Jeff Goldblum (born of a crush on the actor; “the only love song I’ve ever written”, jokes Brown) slinking into the laid-back drawl of Subterranean Shut In Blues (a riff on Dylan for the stay-at-home generation) and the Jack White-spiked delivery of How It Ends (a redwood casket sendoff in song form, wherein perhaps the casket has been struck by lightning).

Similarly, though the analog rock-’n’-soul signature sound of previous Mattiel iterations lingers (the opening twangs of Blood in the Yolk — an eerie, stream-of-consciousness tale of doomed love and eggs — hold up a fleeting, minor-key mirror to 2017’s Count Your Blessings, and the warm brass interludes of Lighthouse, an ode to navigating through sirens and soured fruit together, hark back to early songs like Baby Brother).

Swilley’s input wears many other guises. Mid-tempo numbers such as Wheels Fall Off (glassy chimes and a laid-back beats a bed for Brown’s cortisol-laced words) and Cultural Criminal (organs, haze and cool detachment backing a snappy critique of echo-chamber politics) pay heed to a life spent listening to hip-hop; On the Run honours the country-guitar styling of the Southern States; You Can Have it All strolls briefly into, and then swiftly back out of, psychedelia’s domain, and Other Plans packs Gainsbourgian drama in miniature.

And there is no sense of hierarchy imposed on this beautiful soup of influences: contemporary pop stars revered just as much as more traditional pin-ups. “Party in the USA / Party on the Hudson Bay / Party in the fast lane”, Brown sings on Boomerang, winking in the direction of the heavy machinery-straddling megastar Miley Cyrus. “Jonah and I live in worlds where we don’t judge each other for what we like, even if it’s ‘not cool’ — that’s not even part of our language. I think it’s really cool to work with someone else who can love like … Miley Cyrus as well as Leonard Cohen,” Brown says.

Swilley puts this wide palate, in part, down to the place they call home. “I definitely feel like being from Georgia allows us to have a certain way of approaching music.” Brown chimes in: “We haven’t really highlighted where we’re from in the past two records, even though those were also written in Georgia. There’s so much great art and great music that’s come from Georgia, from all different types of genres and all over the state — take R.E.M. and OutKast: there’s this weirdness that I can’t really put my finger on.” Swilley concurs: “It’s the same with The B-52s, The Black Lips … it doesn’t feel like L.A., it doesn’t feel like New York, it feels like another planet. We’re not really in a ‘scene’ here in the same way. You have to make your own sound, create your own identity.”

And it is precisely the forging of Mattiel’s distinct musical identity that Georgia Gothic signals; its members guiding each other ever-homewards not just in a geographical or sonic sense, but spiritually, too.”